Swiss Watch From The Back Shelf

Of Boland, Endo, and a rare species

Fire in Babylon starts with a war cry. The words are hard to grasp, but the phonetics cut through the frame. It’s a chorus of men reciting a tribal scripture. Simmering underneath is a bed of single-note percussion, played on a taiko, evoking the rumble of a distant storm. The first visuals are of a lanky male1, in Hawaiian shorts and a bare chest, rolling his arm over on a beach in Jamaica. The documentary cuts to grainy footage from an old Test match. A bouncer whistles past an English batter’s nose. Quick, steep, close enough to smell the leather. The batter swings backward to evade. Back on his feet, he springs his eyes wide, trying to reset some balance before the next ball comes hunting.

Tony Grieg and Geoffery Boycott are on commentary. They tell us that the West Indies bowlers are charged up. On the second ball, the batter doesn’t even pretend to try; he just pulls his head away like a boxer dodges a punch. Another close shave. That drum keeps hammering underneath everything, getting louder, the storm coming nearer.

The third ball is the crack of lightning. Straight into the jaw - too quick, too steep, too venomous. Those who saw it live know the details of this scene instantly. Those who didn’t have found its glow on YouTube. It’s a famous passage of play: Courtney Walsh versus Robin Smith, Jamaica, 1990. Geoffrey Boycott, with his Yorkshire vowels, plays the weatherman: “Look at the eyes, the concentration. Yeah, this is fast bowling.”2

He would know. Nine years previously, he was at the wrong end of possibly the meanest and fiercest over ever bowled. Boycott is 84, so it won’t be advisable to spook him, but mention Michael Holding and Barbados, and you’ll see a bead of sweat running down the side of his forehead. Holding’s first ball spat off the pitch and hit his hand, the next few hit him on the thigh, chest, and throat. The sixth ripped his stumps out of the ground. This capsule of six balls makes all-time lists, and got a passage to itself in Whispering Death, Michael Holding’s first autobiography that's now out of print.

Walsh and Holding’s clips have developed a few smudge marks, the colours are pale, but the story they tell holds true even for today’s 4K cricket. Fast bowling, bowled at a proper pace, is cricket at its most primal. And when delivered with sustained pressure, questioning the batter’s ego, pride, and reflexes, before even getting to the technique, it is also cricket at its best.

This has been a good fortnight for fast bowling. The show started at Lord’s. Jasprit Bumrah scythed through England’s middle order on a bland surface. The Lord’s Honour’s Board, that prestigious plank of wood3, now has his name inscribed on it. We watch Bumrah so often, and yet, it is never not astonishing how good he is, how few answers batters have for him. The fear he induces isn’t mortal, but existential: What’s even the point of batting when he has the ball?

But Day 2 is when it got sensory. Jofra Archer, born in Barbados, is no Holding or Walsh, but he is a proper fast bowler. He bowls pace, and he makes batters hop, skip, and jump. As he stands at the top of his mark, shuffling the ball in and out of his right hand, seam upright, the crowd starts emitting a sound. It’s the sound of anticipation, the whoosh of approaching thunder. Something’s going to happen. The batters feel it in their feet, move their legs in exaggerated motion to shake off any stiffness before a red missile arrives at 90 miles per hour, addressed to their throat.

This week, Archer returned to Test cricket after four years of injury layoffs. He was finally ready; as were we. London was hot and sunny, which was a bummer because some dark clouds would’ve created the perfect ambience. But we made do with the props we had. The Lord’s crowd, always gentle, grew in volume as Archer leaned on his mark to start his run up. Six years back, at the same venue, from the same end, he had bowled a spell from hell to one of cricket’s greatest pair of eyes. It ended in MRI scans and concussion. Here, it took him three balls to nick off India’s bright young opener.

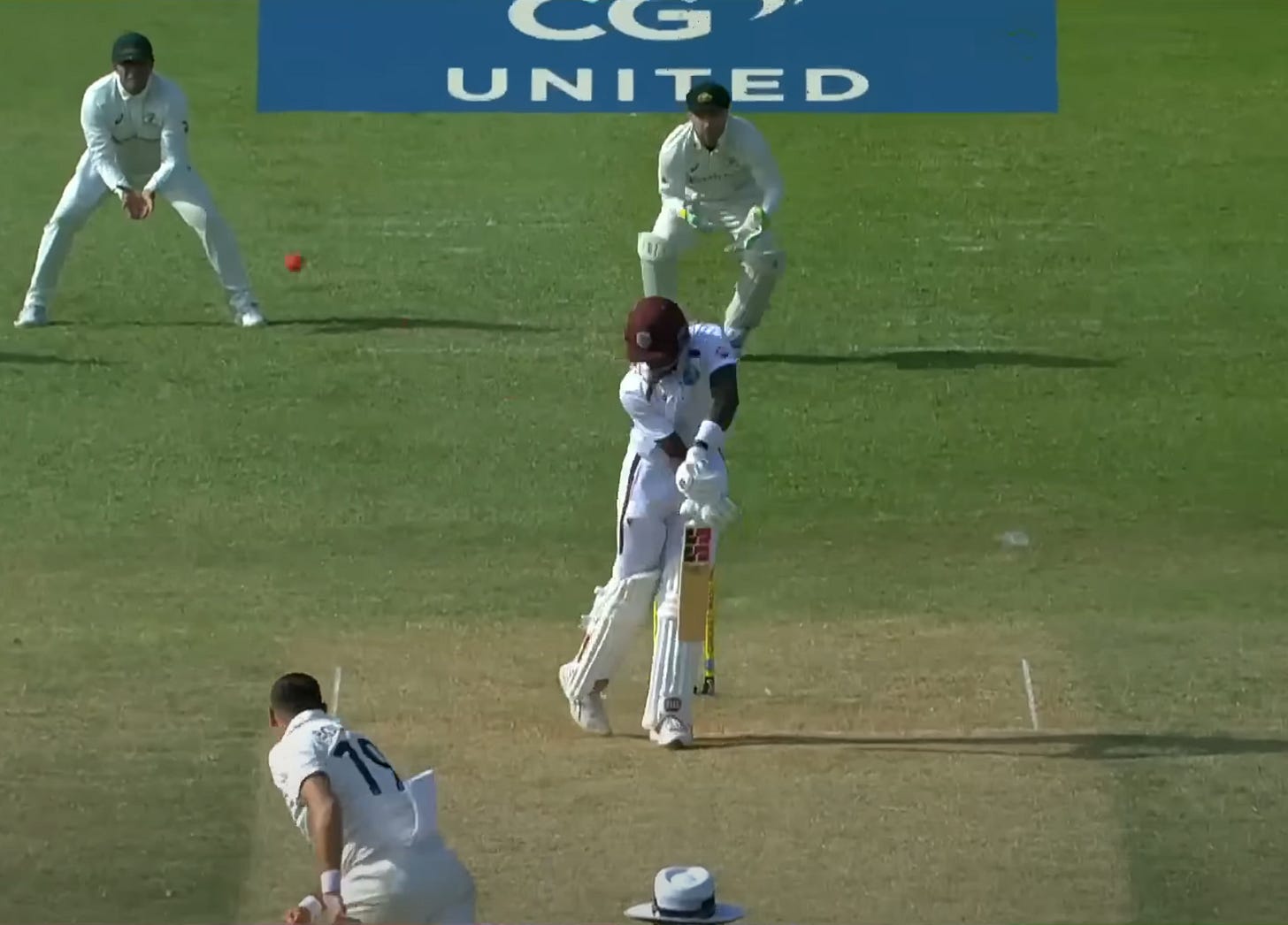

Some 5000 miles west, in Jamaica - the land of Holding and Walsh - the West Indies were playing Australia in the third Test of their series. Australia had won the first two Tests. In the last innings of this match, the West Indies needed 203 to salvage some pride and finish the series 1-2. They got shot down for 27. Yes, not a typo. All out for 27 of your cricket runs, with a scorecard reading like a phone number. The protagonist of this show was Mitchell Starc, in his 100th Test, with six wickets. Around him, Josh Hazlewood helped himself, Pat Cummins too.

Amidst all of this, the complete antithesis to fast bowling’s Main Character Energy, is Scott Boland. Ambling in, eyes locked on a coin-sized spot on the pitch, and sending precision beams at 80 miles an hour. At Jamaica, he barely gave a run and casually finished with a hat-trick. Muted celebration, embarrassed smile, some high fives, and off he went.

Man, I love Scott Boland.

He has a toothy grin that stops at his dimples. When he smiles, he rarely ever makes eye contact, looking sheepishly at the ground instead, like a child caught with too much ice-cream. He hesitates to celebrate his wickets, and gets embarrassed when the crowd serenades him. He is a proper athlete, as you expect an Australian cricketer to be, but doesn’t have their overwhelming physicality. His broad chest has earned him a nickname - Barrel - but he hides it under fully-buttoned shirts. I’m confident he’ll be impossible to spot at a supermarket.

Boland is a rare sight in Australian whites. Since his Test debut in December 2021, he has played just 14 games, most of which have come as an injury substitute. He’s almost certain to be on the bench when Australia line up for the first Ashes Test in November. And to think, no male, since Sydney Barnes waved his goodbye in 1914, has picked more wickets than Boland’s 62 at a better average.

Boland’s is the curse of being an outlier around three graph-breaking gods of the game. Mitchell Starc, Pat Cummins, and Josh Hazlewood are exactly the kind of athletes you think of when you think Australian fast bowlers. All 6’3” and taller, lean, rapid, relentless, and make batters fear for their noses and toes. Between them, a thousand Test wickets and counting. They are the rightful baton-carriers in a line stretching back through Mitch Johnson, McGrath, Thomson, and Lillee.

The fourth bowler in the current Australian lineup is Nathan Lyon, the off-spinner, with 562 Test wickets. Scott Boland will be the first to tell you, with a disarming smile, that there aren’t too many ways to shoehorn him into the starting XI. So he waits. The most reliable substitute in the world.

At Jamaica, the first of Boland’s hat-trick wickets was Justin Greaves. West Indies are already bleeding at six down for nothing. Boland has a sweet spot where he likes to land the ball: six to eight meters from the stumps. I call it the Bolength™. Too short to drive, too full to cut. Greaves knows this. He sets himself up textbook-perfect, bat and body aligned to defend.

Good choice on most days, grave mistake here. The ball cuts ever so slightly left upon pitching, completely disorienting Greaves, and turning his solid base into bent thermocol. Edged, caught, gone.

Shamar Joseph missed a straight one the next ball. After him came Jomel Warrican. Four slips, a gully, and the keeper crouching behind him, waiting for an edge. Boland pitched the ball exactly where he pitched the Greaves ball. Except, this one darted inwards. Cue: the familiar rattle of the wooden stumps, bails flying out of frame. Hat-trick.

This is Scott Boland distilled. There is a discernible pattern to his wickets: batters are caught off-balance, having to adjust very late. All of them monitor his wrist-position and the ball’s seam, bringing their career’s worth of experience to predict line, length, and movement of the ball, until it deviates at the last split-second. It’s one thing to navigate spinners doing this at 50 miles an hour. One can hang back on their rear leg and play after the ball moves. At 80 miles an hour, you’re wrong before your brain can trigger the alarm synapse.

Yet, we only get him in glimpses. No extended runs, no chance to watch him grind a batting lineup to powder across a full series. Just these perfect cameos, like an artist who only releases chart-topping singles every couple of years.

Good teams have excellent bench strength. This summer, India are playing a Test series in England without the insurance of Ravichandran Ashwin, but they can’t make space for Kuldeep Yadav. At their high peak, Australia made Mike Hussey wait. Manchester United owe their finest moment in the last fifty years to the sharp instincts of two substitutes who would’ve walked into most starting lineups in the world.

A couple of weeks back, I was discussing analytics and recruitment with the sporting director of a European football club. We landed on Wataru Endo of Liverpool. And this face on the other side of the Zoom call told a story.

In the summer of 2023, while rebuilding their midfield, Liverpool were in the market for a defensive midfielder. The marquee names were proving too expensive, but Liverpool were desperate. A long, futile chase later, they went to Wataru Endo, a Japanese international playing at VfB Stuttgart. Stuttgart had finished the previous season 16th on the table and only saved relegation through a playoff game. Endo’s industry, however, showed up on a lot of scouting radars. He just wasn’t high-profile enough. Eventually, Liverpool decided that he was a punt worth taking, especially at the miserly outlay of 15 million pounds.

Endo isn’t your typical gnarly, homicidal defensive midfielder. He is oddly clean in tackling and passing. No run-ins with the referee, no two-foot tackles into the opposition captain’s midriff. Just intercept, pass, and move. But, like Boland, sometimes those skills aren’t enough to make it to the facing shelf.

In his first season, he played 1722 minutes of league football - only about 50% of the time Liverpool spent on the pitch. In his second season, that number slumped to 7.7%. For all his skills, Endo just isn’t at the same technical level as some of Liverpool’s alternatives in midfield. So, he has been assigned a seemingly straightforward modus operandi: come in fresh with 10-15 minutes left, just as everyone’s tiring, and kill the game. Shield the defence, sweep up any loose balls, and break any dangerous attacks from the opponents.

Anyone who has played five minutes of competitive football will tell you - a defensive midfielder’s role is unglamorous, but it’s amongst the hardest things to do on the pitch. It is even harder when the game’s in its final quarter and the opponent is throwing wave after wave of attack. Footballers will also tell you that you know a defensive midfielder is very good when there are no headlines or subtexts about them after a game.

The thing that sets Endo apart, that makes him such a trump card for Liverpool, is that he just doesn’t seem to make mistakes. He is invisible from match reports and post-match Instagram reels. He is a bundle of energy, chases his man like a hound, but blurs from the frame once the battle is won. As you can guess, a lot of people are jealous that Liverpool got him for a lower transfer fee than top teams pay for their third-choice goalkeeper.

There is something very cool about players like Wataru Endo and Scott Boland. No, not the different palette to their peers, not just that. But this ability to immerse yourself so deeply in the team’s colours that an athlete’s basic, innate yearning for a stage to show their talents becomes somewhat irrelevant. It comes at a cost. They won’t get into documentaries and montages. There will be no hand-drawn paintings or statues at stadiums. And it’s entirely possible that, three years from now, people will skim their Wikipedia pages, cherrypick numbers, and call them frauds on Twitter. Endo is 32, Boland is 36, so this gig is probably their last high-profile rodeo.

Imagine turning up for a game and hearing that your opponent’s best guy is injured. You look up the substitute. No one’s heard much about him, no obvious skill to set him apart - else why would he be a sub - and he barely speaks. Won’t you high-five your mate right there? Won’t you feel that victory is now just a little bit closer? And then this bugger starts, and goes on like a Swiss watch. Not a single mistake. Not even when you throw everything at him. This substitute, this nobody, is harder to face than the genius he’s replaced. Because genius, at least, you can plan for. Genius has patterns and preferences. This is just unerring competence from an introvert who smiles at you while tackling you into the ground. Won’t you feel like tearing your hair apart?

The highest compliment I can pay Wataru Endo and Scott Boland is that they’re insanely annoying. Long may their tribe grow.

Been awhile since I came across a ‘Fire in Babylon’ reference :) And excellent piece, as usual!

Scott Boland is more than a backup. He will be picked in several Test matches this summer. The proud Gulidjan man must be picked for the Boxing Day Test in his home state. The selectors know it, they know that cricket needs him.