Sunset

Or is it?

In a few hours, Jannik Sinner will play Taylor Fritz in the US Open men's singles final, the last act of this year’s Grand Slam theatre. They beat Jack Draper and Frances Tiafoe, respectively, in the semi-finals.

These four are lovely, exciting tennis players, but something feels strange. As world number 1, Sinner should be the focus, yet conversations keep drifting to the early exits of number 2 and 3: Carlos Alcaraz and Novak Djokovic. We know that Alcaraz's absence from the final rounds is momentary, a blip in a soaring career. Djokovic, however, is a heavier topic.

This is Novak’s first Slamless year since an elbow injury-ravaged 2017. Take that period away, and he has been a Grand Slam-winning machine for the last thirteen years. Even recently, as a new generation of challengers has caught up with the old guard, he has been in prime form. Three Grand Slams in 2021; Wimbledon in 2022; three more Grand Slams and a nail’s breadth runner-up in 2023. Compared to all of that, 2024 - a year of one final, one semi-final, one injury withdrawal, and one early knockout - feels like a barren wasteland.

For any other player, even at the top rungs of their sport, we’d chalk it off as a temporary rough patch. Anyone can have a bad year. Add a knee surgery to that, and there is good reason for them to not find sustained rhythm. But at 37, with countless miles on those legs, it is impossible to ignore the long shadows cast by Father Time. With every passing game this year, those shadows have only crept closer.

And yet, there is a lot of reluctance about labelling this as a moment of descent, a handing over of the crown. That is down to what we know of Novak Djokovic as a tennis player.

Djokovic wins. On grass, clay, or turf, in freshness or fatigue, trailing by a couple of sets or without breaking a sweat, he just finds a way. In the last decade or so, he has been so impossibly brilliant at winning tennis matches that the lack of jeopardy has felt a bit annoying.

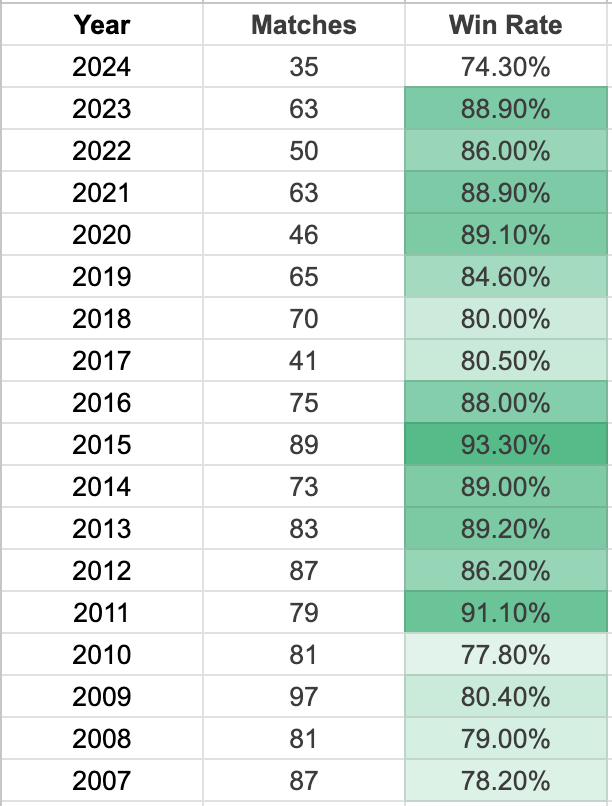

Grand Slam semis and finals, pressure-cooker moments that test the nervous system of most, were routinely executed with the nonchalance of an evening stroll. Barring duels with Rafael Nadal on the Paris clay, I don’t remember the last time Djokovic entered a match as the underdog. No man, in the history of tennis, has a better win ratio across their career than Novak’s 83.5%. Between 2011 and 2023, a period longer than a lot of careers, he won 87% of his 884 singles matches.

At his best, Djokovic’s game is a picture of architectural perfection. There are no rough edges, no shot he can’t play, no blade of grass he can’t reach. He can switch between tempos and styles with the comfort of a virtuoso drummer. It’s like he was lab-engineered to perfection - perhaps the only way to emulate and eclipse the two great artists of his generation in Roger Federer and Rafael Nadal.

We saw this Djokovic at the Paris Olympics. It wasn’t just a glimpse; he prowled like an apex predator. Through the early rounds, to the semi-finals against Lorenzo Musetti and the gold medal game against Carlos Alcaraz, Djokovic was playing like this was 2019 or something. It was his last shot at the elusive Olympic gold, and boy did he bring his best.

A sport looks different when the greats flex their muscles. Frank Lampard and Rio Ferdinand, while gushing about Lionel Messi once, mentioned how he seems to play football in slow motion. In situations where others would stretch and rush, Messi is calm and precise. His feints aren’t wasted, his pass finds the exact target.

When the game moves at a hundred miles-an-hour, finding the extra millisecond is a matter of better anticipation. If you watch back footage of tennis greats at their most dominant, you will find them either pushing and pulling their opponents, as if controlling them on a string, or just being able to magically predict where the next shot will land. At his best, Djokovic does all of that, every match.

Which is why the Olympics, otherwise a blind spot in the quadrennial tennis calendar, sticks out this time. Outside that week, Djokovic hasn’t quite found that zone this year. His win ratio in 2024 is his lowest since 2007, when he was 20.

Around him, the rivals are getting stronger. Carlos Alcaraz comes with more arrows in his quiver every time you see him, and Jannik Sinner is moulding a game as spectacular, precise, and unforgiving as Novak’s himself. Alcaraz is 21, Sinner is 23. A generation younger than Novak. This year, it showed.

The next Grand Slam on the horizon is the Australian Open in January next year. I suspect, with recent results, its importance for Djokovic will have amplified. Not that he’d mind. He won his first Grand Slam there back in 2008, and has since added nine more Australian Open titles. The Melbourne Park court is like home for him. He can close his eyes and paint the exact shape of the stands or the precise kerning of the KIA logo, and tell the inches between the service line and the backboard.

Besides, the hard court surface is tailor-made for his game, even more so now. Clay and grass amplify the physical margins between him and the younger bunch; the cushioned acrylic at Melbourne gives him a balance between speed and grip. There is no other place he’d rather start the next lap from.

When he touches down in Australia, the questions will come thick and fast. How much longer does he plan to compete? Is 2024 the first hint of an approaching sunset? Does he have enough left in the tank to go toe-to-toe with a crop of rapid 22-year-olds?

He knows this part of the movie all too well. For all his career, he has been told that he is neither as good nor as likeable as Nadal and Federer. Now the same comparisons are with Sinner and Alcaraz. And while he has, sometimes desperately, sought everyone’s adulation, the lack of it hasn’t ever affected his game. He uses the jeers and jabs like an energy drink. The louder the noise, the better he gets.

That said, at this stage of his career, silencing critics is probably low on his priority list. The real battle is internal. He’d want to prove to himself that he’s still good enough. That this next challenge, of keeping up with two exceptional young tyros, is not a bridge too far.

The greats do this weird thing - when they see a mountain, they immediately start planning how to scale it. Even the idea of it being too high, too treacherous, or too demanding on their body doesn’t register with them. That is why you see so many of the greatest athletes play long into their twilight years. They keep pushing, not necessarily because they are reluctant to step aside, but because they don’t actually think something is unachievable.

In sports, we often blurt out a cliche that goes like, “It’s not over until it’s over.” This is little more than a truism, and often falls flat when met with impending reality. Try saying this after Andy Roddick loses two sets, within an hour, to Roger Federer at Wimbledon; or after India lose Sachin Tendulkar in the first over of a World Cup final, while chasing 359 against the best ODI team ever assembled. This is the reaction you'll get.

But, with Djokovic in working condition, as long as he's able to hit or return a serve, you can keep dishing this out at your house parties and WhatsApp group chats, and not one sane person will disagree.

One of my all-time favourite opening lines, across genres, is from an essay on Djokovic, written in the hours after his epochal Wimbledon victory over Roger Federer in 2019.

“Novak Djokovic has a way of winning even when he’s losing.”

There may or may not be another Grand Slam final for Novak Djokovic. But he’s probably the only person who can flip the script at the age of 38, with a body that’s beginning to chip at the edges. And even if it doesn’t quite happen as perfectly as he’d like, he will stretch the kids to their last drop of energy and ability before he walks. It will be a marathon five-setter either way. You just know it.

The Michael Jordan gif is priceless haha.

Terrific writing, as per usual, Sarthak. Those win percentage numbers are staggering - great idea to use them the way you did in the piece.

...is like no other. But every crest has a trough ..and Nole is nearing his.