Hell in a Cell

Jump!

Netflix’s new show, “Mr. McMahon”, opens with carousel of ex-wrestlers getting mic’d up for interviews. A pulsing synth bassline underscores the tenor of the series. It’s your classic cold open, a rapid-fire teaser of what’s to come over the next 300 minutes.

As the episode cuts to documentary footage, the word “business” flashes on the screen within ten seconds. It doesn’t take long to strike home that business, in this context, is less a word and more a leitmotif.

Vince McMahon is unapologetic. At every turn, every conflict, he repeats his credo: World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE) is a business, and he’d sacrifice a limb for a bump in the ratings. Each decision serves this singular, green-tinted purpose.

The company broke boundaries with its storylines and contracts. Wrestlers were happy to cede control of their on-stage narrative, but they probably did not expect the kind of physical toll they were signing up for. They were regularly pushed beyond their breaking points. Bret Hart performed through concussions. The Undertaker had to conceal a leg injury that made it hard for him to walk. Pain was a familiar and constant shadow, its edges only softened by pills and needles. Steroids were as much part of the staple as stretching exercises. McMahon’s message was simple: swallow the painkiller or find yourself a new job.

There was no recourse either. The WWE, in its fledgling and flourishing years, was an entertainment product and not a sport. Vince McMahon left no room for athletic regulations and oversight bodies. The wrestlers just had to do as McMahon wanted them to.1

The conditions got worse with the company’s soaring ambition, and it took some brave journalists to draw attention to life behind the black curtains. During the peak of pro wrestling-craze in the late '80s and early '90s, Ted Turner's WCW dangled a more humane schedule like a carrot on a stick. It eventually became a powerful bargaining chip for wrestlers struggling to breathe in WWE’s toxic chambers.

The house has since been cleaned, at least in some rooms. Wrestlers are better protected with worker regulations, and there is more scrutiny on the demands placed on them.

McMahon’s playbook, however, has been adapted in many theatres.

In September, this year, Manchester City and Spain superstar Rodri spoke publicly about major discontent amongst footballers. He hinted at an imminent strike if administrators don’t quickly fix the problem of top teams having to play too many games. Even from the quieter corners of English football, Southampton's head coach Russell Martin nodded in approval. His team has lesser matches to play, Martin conceded, but he agreed with Rodri’s sentiment.

“I think something's going to give at some point. I think that the quality will be diluted at the top level. The top players... you'll see less of them because of injuries, so I think he [Rodri] has a very good point and I think it needs to be looked at - the welfare of the guys playing internationals and the Champions League.”

In the time since, Rodri ruptured his anterior cruciate ligament - ruling him out for eight to nine months - and FIFA President Gianni Infantino announced a new competition through an Instagram reel in collaboration with DJ Khaled.

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is a short band of tissue that connects our thigh bone to our shin bone. It is most commonly stretched during sports that involve sudden stops and changes in direction — think basketball, football, or tennis. And when it tears, the consequences are devastating.

Nearly thirty players missed the 2023 Women’s World Cup because of ACL injuries.2

During the 2022-23 men’s Premier League football season, there were four ACL injuries. The 2022 FIFA World Cup was scheduled in the middle of that season, forcing the regular schedule to compress and stretch like an uneven resistance band. Do your causation-correlation juggling, but the number of ACL injuries in the next season - 2023-24 - jumped to 10, part of an overall 11% rise in injuries across the Premier League.

At a 2024 conference, David Terrier, the European president of the FIFPro Players Union, sounded the alarm: “There is an emergency – we are in danger. We're seeing a rise to dangerous mental and physical fatigue.”

A Players Union report in that conference also highlighted that “50% of respondents said they had been forced to play while already carrying an injury, while 82% of coaches said they had fielded a player they knew required a rest.”

Déjà vu.

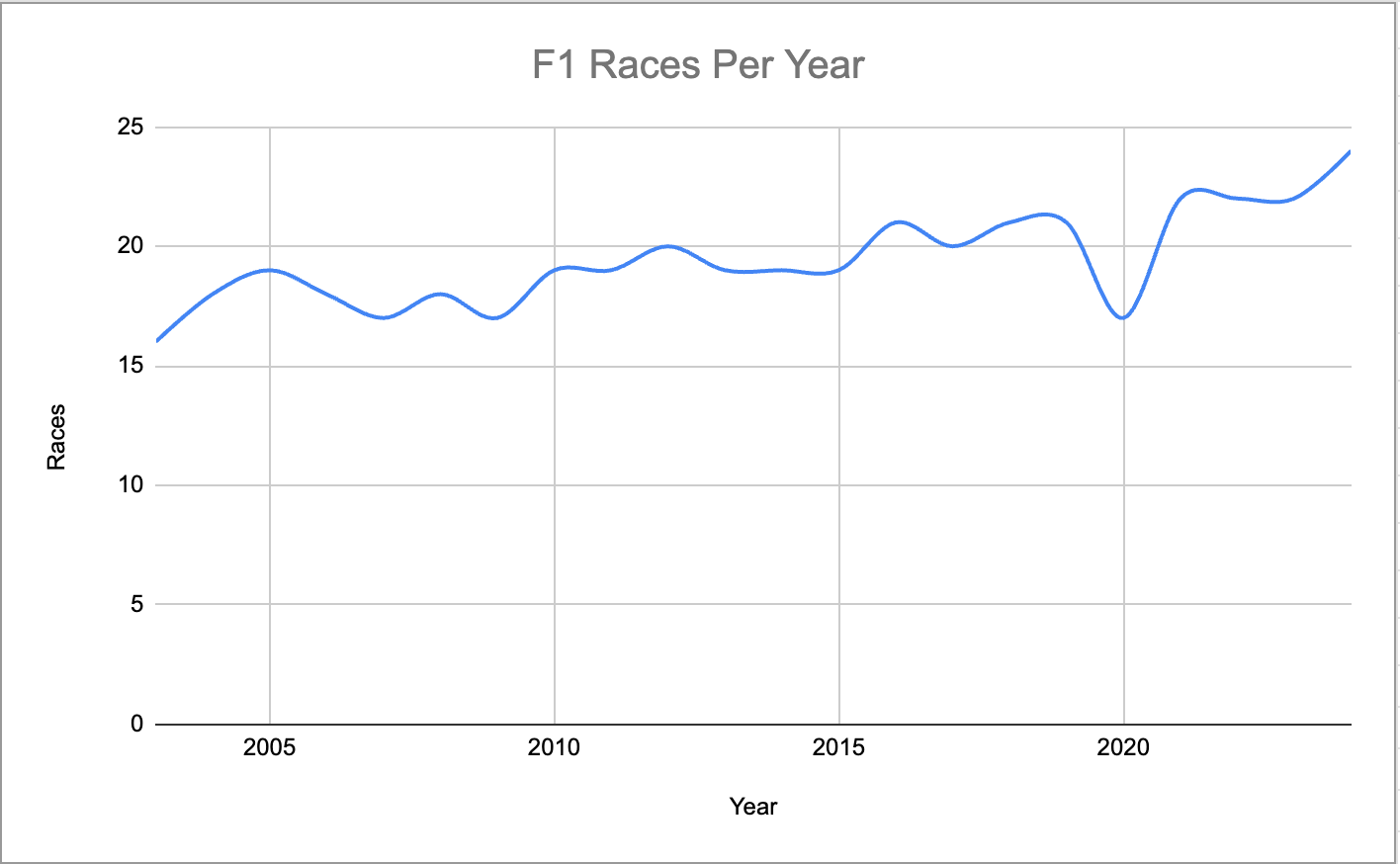

Formula One is following the plot with mechanical precision. The sport has seen an explosion in its popularity thanks to Netflix's “Drive to Survive” - a fly-on-the-wall docuseries that turns its high-octane world into a soap opera on wheels. Liberty Media, commercial rights holders of F1, have capitalised by adding races across the world. The Middle East has new venues; a bunch of classic European circuits have been revived; and the USA now has three races, one of them in Las Vegas. The 2024 season will feature a record 24 races.

The chorus of complaints spans generations, from 27-year-old double World Champion Max Verstappen to 42-year-old veteran Fernando Alonso, who made his debut way back in 2001.

“When I started we had 16 races, then it was 18 at some point, and then I think when Liberty [Media] came it was like a message that we have 20 one season and that was absolutely the limit, 20 races,” Alonso mentions. “And now we are up to 24 and this is not sustainable for the future. Even the world champion thinks this is a little bit long, the season. Imagine for the rest of us, we go to the races in the second half for nothing, there is no incentive to fight for anything.”

Cricket, too, has jumped on the bandwagon, albeit with a lighter load. The top men’s teams - England, Australia, India - have to play a disproportionately high number of matches. They're the biggest cash cows in the cricket meadow, and administrators are milking them for all they're worth.

Add the franchise tournaments to this, and you have a congested schedule which leaves little breathing space for fans, nevermind the players. Thankfully, the rhythms of the international cricket calendar have allowed the top players from the Big Three to cherry-pick their tournaments. Pat Cummins recently sat out an ODI series against England - unthinkable for Australia’s best cricketer and Test captain even a decade back.

You get the pattern. Sport is unscripted theatre, where each day the scoreboard resets to zero. Its raw drama and unpredictability is catnip for moguls with deep pockets and a flair for the spectacular.

When cinema theatres, and later television, became mainstream, sport lost a chunk of its core audience and a boatload of its potential viewers. Entertainment was available at a button’s tap, with a guaranteed serotonin hit. Unless you really liked sports, there was no reason to spend ninety minutes watching twenty-two men chase a ball.

Like any entertainment product, sport has long been making moves to glam itself up and become more palatable. Football introduced tie-breakers and golden goals; cricket unveiled limited-overs formats; Formula One gave drivers faster, sleeker machines each year. Opening ceremonies became more elaborate with every passing event.

It feels a bit like praising Hitler for his oratory skills, but Vince McMahon was ahead of his time. He identified professional wrestling’s potential as a bridge between athletics and theatre. He blurred the boundaries and catered to both, serving up a cocktail of flesh-to-flesh combat, music, fireworks, chairs to the face, blood, and twenty-foot jumps. We were hooked.

McMahon wanted to reach stratosphere, and he forced everyone to train to become astronauts, or at least look like they could bench-press one wing of the International Space Station.

Decades after the cracks in McMahon's design became apparent, his formula seems to be the industry standard. The human cost is brushed aside as collateral damage, like a broken table at Wrestlemania. The players have less and less time to recover during the off-season? Well, someone has to play in the meaningless Confederations Cup. Kit up!

The CEOs will have a riposte ready. They'll tell you that sports is now part of the content industry, competing for every penny with Marvel and DC like they’re all participants in some sort of financial Hunger Games. Hell, even Netflix, Amazon, and Apple have lunged to have a piece of this pie.

For a business, they’ll say, the only way is up. Sure, scale is good. But here’s the problem. Good scaling invariably balances the vertical with the horizontal. And that happens when the component parts are built up for scale too. Without proper strength and endurance training, a half marathon isn’t a workout but a recipe for injury.

Vince McMahon couldn’t care less about the limitations of a human body. Wrestlers were replaceable, rechargeable batteries in his remote. Many sports operate similarly now.

The FIFA or ICC presidents may not speak the same words as McMahon once did - suggesting that deaths and injuries amongst wrestlers were not his responsibilities - but they’re all reading from the same screenplay. It is unlikely that they will think of Rodri’s cruciate ligament as a metaphor for what sport truly feels for its most important commodity.

Netflix produced “Mr. McMahon” as a hit-piece on a deeply problematic person and industry. But as the final credits of roll, one can't help but wonder if we are witnessing the epilogue of McMahon's dynasty, or merely the prologue to sport's next evolution.

An entire book can be written about employee exploitation in the WWE

Women’s football is suffering from an ACL epidemic.

The only sport I used to watch was tennis and that too, in the 90s. But my daughter was a huge WWE fan and like every true fan, hated McMahon, for the reasons you have so clearly expressed here. If money is the only bottom line then joy is eventually lost in my ‘not an expert’ opinion.

As a fan, I'm generally overwhelmed with the amount of live sport there is to watch, makes me wonder how far can they go until the quality takes a hit and fans stop showing up. Yes, there is widening talent pool to replace, but can they easily move on from rooting for one player over years to another one (most fans are equally tribalistic about individuals as they are about their teams).

Quality writing 🔥, enjoyed reading this piece.