Notes From the World Cup: Semi Finals and Noise

India vs New Zealand, Navi Mumbai

It was the simplest of plays that ended the match. Final ball, target out of reach, Rosemary Mair heaved and Smriti Mandhana caught. A dominant performance punctuated by a finely marked full-stop. India were through to the semi-finals of the Women’s World Cup.

The crowd let out a roar, fitting for the progression. On the ground, lit up bright under the DY Patil Stadium’s low floodlights, the eleven women in blue ran towards each other with wide smiles. There was no exaltation, no delirium. The win brought relief.

The DY Patil, a multi-purpose stadium in Navi Mumbai, was packed through this weekday. The official attendance was 23,180 - a record for a group stage game at any ICC women’s event. Earlier in the day, Smriti Mandhana and Pratika Rawal obliged with centuries, and Jemimah Rodrigues made the office and college bunks worth their trouble with a sparkling 76. And then the evening rain doused whatever hopes New Zealand might have reserved of mounting the chase.

The win against the White Ferns was India’s third out of six group-stage games at the World Cup. Which means, regardless of their result against Bangladesh tonight, they will finish fourth on the table, set up to face table-toppers Australia in the semi-final.

For ears tuned to other sports, semi-finals at a World Cup has the ring of achievement. It’s not something to be scoffed at. But, in an eight-team World Cup - hardly worldly - fourth place doesn’t sound like a triumph for this team.

Firstly because they could’ve, should’ve, finished higher. Out of India’s three losses, two - the South Africa and England games - should’ve been victories, especially the latter. They let go of advantageous positions through ordinary decision-making and a gap in squad balance. Finishing higher doesn’t guarantee an easier semi-final per se, but you carry a strong tailwind. India won’t quite have that.

And secondly, Australia, England, and South Africa have all looked more complete, found extra gears in crunch moments. You could also make a case for New Zealand getting the raw deal thanks to the Colombo weather. Who knows what could’ve been if they completed a few more of their games? Maybe that explains the sensation of unease as we begin the knockout week.

Reaching the semi-finals isn’t news. The Indian women have made the semi-finals or better in four of the last seven ODI World Cups, three of the last four T20 World Cups, and won silver at the 2022 Commonwealth Games. This is, beyond doubt, a strong team.

With every passing tournament, that’s led to greater expectation and anxiety. To make things worse, the gold medal’s been a mirage. Just from memory, India slipped from touching distance at the 2017 ODI World Cup and 2022 Commonwealth Games finals. Those are the kind of scars that make familiar slips feel like déjà vu. And, honestly, the team has given a lot of that in this tournament.

In the last week, as India stumbled through three consecutive defeats, the agony from watching eleventh-hour collapses and inexplicable tactics, like reruns of an old show, found expression.

Some of it was refreshing. Pratika Rawal’s strike-rate and dot ball percentage were analysed, as were Richa Ghosh’s entry points. Coach Amol Muzumdar was asked about the Pratika-Harleen combination at the top of the order, and how their similar batting styles could stifle India’s run-rate. Captain Harmanpreet Kaur was asked about the playing combination: carrying just five bowling options is a recipe for disaster.

These are all crucial questions. Not merely for the sake of placing a high-performance team under a magnifying glass but specific to the issues that keep chipping at this unit. Our admiration can sometimes cloud our vision, and good reporters help break through that.

Coverage like this also has major downstream velocity. News publications pick up on it, broadcasters run tickers. Blue-ticked clout chasers on social media make long threads. And suddenly, everyone has a conversation-starter. Watchers new to Women’s cricket are asking whether Shafali Verma should’ve been dropped from the squad. Others, who are a bit more clued-in, explaining combinations with records and stats. This, right here, is the whole point of a World Cup - to get people talking.

My friend, Ruhin, works in advertising and understands people and behaviour. He is encouraged by the decibel levels. For now, it’s in the greens, sometimes touching the yellows - signs of healthy, necessary buzz around a team that warrants more attention. My worry is that there’s a point, not too far away, when the noise touches earbleed frequency. Today’s technical analysis is one bad shot away from becoming tomorrow’s character assassination.

Especially with this team. Each tournament, they are placed under audit, asked to re-earn the right to be taken seriously, prove that they deserve their salaries, their stadium, their once-in-a-while primetime slots. And when they slip, like sports teams do, the knives come out with a snap.

We’ve seen it all this week. First came the experts dissecting technique. Then the pay-gap philosophers, calculating what these women cricketers were worth, per failed shot. By midnight, the real professionals had arrived - the ones who know seventeen different ways to call a woman cricketer something other than a cricketer.

According to FIFA, half the abuse female footballers received at the 2023 Women’s World Cup was sexual, sexist, or homophobic. The other half, presumably, was just regular viciousness. Firdose Moonda has written about Sinalo Jafta, the South African keeper who faces what Moonda calls “an intersectional triple-whammy” - professional sportswoman, black, and built like an athlete rather than a model. The abuse extends beyond the players themselves. Ask Anushka Sharma what happens to her social media pages when Virat Kohli gets out cheaply.

Here, even outside the cesspit of anonymous accounts, the torrent of barbs picked up with every missed shot. Someone on my timeline called the team embarrassing, someone else mediocre, and senior sports journalists - who hold editorial positions at national dailies and media channels - used a lot of adjectives between disgusting and undeserving. This for a team that had won an ODI series in England three months ago. Memory, obviously, is inversely proportional to disappointment.

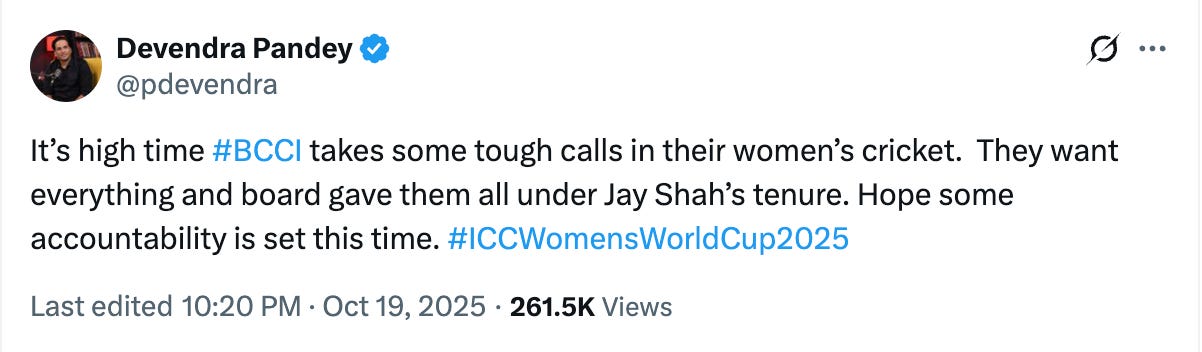

One senior pro diagnosed the problem: spoilt kids who demand and receive gifts but never deliver returns their metaphorical guardians deserve.

For starters, it is downright hilarious to accuse the Indian women’s cricket team of benefitting from nepotistic gifts while mentioning Jay Shah in the same sentence, but it’s worth unpacking the sentiment to check out the sticks we’re bashing this team with.

The first one has the label “equal pay.” In October 2022, Jay Shah, then-Secretary of the BCCI, announced that Indian cricket had shattered the glass ceiling of gender-bias by giving its men and women international cricketers equal pay. The women would now be paid 15 lakh INR per Test, 6 lakh per ODI, and 3 lakh per T20I. The fine print was neatly concealed: the pay parity was only limited to match fees. The annual contracts bore no similarities, not even in the number of digits.

The facilities couldn’t be more divergent. Since 2016, this team has been asking their board for a dedicated sports psychologist. Last summer, during their preparation for the 2024 Women’s T20 World Cup, the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) arranged for a sports psychologist to conduct a few sessions, as a favour. The further you go through the history of women’s cricket in India, the more you recognise that undeserved privilege and them in the same sentence makes for an oxymoron.

Then there’s the Women’s Premier League - an IPL-equivalent franchise T20 tournament that finally saw the green light years after Australia, England, South Africa, and New Zealand had launched their leagues. The league has been a success, no doubt, playing to packed audiences across the country. It has changed lives.

But, it’s just been three years. History has shown us repeatedly - while progress is a valid expectation, immediate success isn’t. Throwing money isn’t a magic spell. Abhinav Bindra, speaking to the IndianExpress after the 2024 Paris Olympics, laid it out: “Resources being allocated is only a simple enabler, and you need it. I mean, how else do you do it? You need money for training, to compete, travel, for the larger performance support stuff. But that doesn’t mean that it’s a vending machine. You can spend more, you can spend less. It’s not going to guarantee you success.”

My favourite story about continued bottom-up investment in a sport comes from Japan. In 1992, the Japan Football Association (JFA) launched the J-League to professionalise Japanese football. They started how everyone does, luring celebrity ex-footballers over, but began major structural investments in parallel. They sent scouts to football hubs in Europe and South America to identify the best practices. The result of this exercise was the 100-Year Vision - a roadmap stretching to 2092, the J-League’s centenary, for Japan to win a FIFA World Cup. One hundred years.

Like Prem Panicker wrote here, after the Paris Olympics, “Sustained sporting excellence is based on mass support, grassroots development, and funding -- and it is this trifecta India needs to work on, systematically.”

Honestly - and Prem will attest to this, as someone who has had a ringside view of Indian sport for three decades - the conversation gets tiring after a point. Not because of the cadence or repetition, but because of its futility. Indian sports administration operates on the timeline of a cigarette break. Tomorrow is long-term planning; next week, visionary. I’ll give you a sample.

Currently, the Indian men’s football team is ranked 136th in the world, 65 places below Cape Verde - an island country with less than half of Bangalore’s population. Cape Verde are going to next year’s FIFA Men’s World Cup, while India have failed to make it to 2027’s Asian Cup.

Amongst the laundry list of nagging issues is a lack of decent centre-forwards. It got so bad Sunil Chhetri was asked to come out of retirement until good alternatives can be found.

To solve this problem, Kalyan Chaubey, the All India Football Federation chief, suggested a - hold your breath - crash course. “We want to get a top striker in the world,” he said. “We will identify 5 or 7 Under-23 strikers and give them a few days’ crash course in finishing.” Incredible stuff.

Being a top-50 football team, or competing with the Australian or English women’s cricket consistently, requires an ecosystem that looks at tomorrow and next month and next year, that creates a robust foundation for the senior and age-group teams, backs them in every way all the way, and then backs the next in line. Because that’s what you ought to do, if you have serious sporting ambitions.

As of today, we’re lucky to call the Indian men’s cricket team structurally supported. The Indian women’s team, far from it.

If India’s World Cup ends how we expect it to - win against Bangladesh, loss to Australia - there should be applause and scrutiny in equal measure. Maybe more scrutiny, even. To love something is to look it straight in the eye. Keep the questions coming. Ask why they couldn’t foresee the problems with their team combinations. Ask why they couldn’t be more agile with batting partnerships. Ask about plans, executions, tactics, everything.

But, for god’s sake, shut up about whether they deserve what they have.

Thanks, Prem.

And I agree. So many countries are able to treat different sports and genders as their own thing. What England do with the Women's Hundred is so good. Ditto, Australia and the WBBL.

Well put, Sarthak.

I see why organisers tap into fans of the men's game to expand women's sport; it sadly comes with shallow engagement and an inability to view the game in its own right.

While there is a uniquely Indian problem here, I think there is a lot we can learn from sports like rugby on how to grow the women's game independently. Their recently concluded Women's XV WC did some mind-boggling numbers, and the organisers were vocal and intentional about it.