Lionel Messi Comes Home

On belonging, and what it means to be seen by the place you love the most

On the night of September 4th, 2025, the Estadio Monumental in Buenos Aires was draped in white and blue. Argentina were playing Venezuela in a World Cup qualifier that didn’t have much hinging on it. Argentina had already qualified for next year’s main event; Venezuela, ranked 46th in the world and 7th in South America, were fighting for a late playoff spot.

For Buenos Aires, however, the football was incidental. The stadium was packed two hours before kickoff. On the south stand, a banner in thick black font screamed: GRACIAS POR TODO MI CAPITAN. Ten feet to the left, a poster with his face covered the gap between two floors of seating. Every back in the stadium carried the same name, the same number 10, like a congregation dressed for a farewell.

El Capitan obliged, scoring twice. He spent ninety minutes bending space around him the way he always has, making the impossible look pedestrian, sprinkling stardust with every dribble, being Messi. When the final whistle came and seventy-eight thousand voices cracked the night air with songs they’d been saving up, Messi’s face went from his typical in-game stoic to a half-smile and a softening around his red-ish eyes. The way a man looks when he finally arrives at a door he’s been walking towards his whole life.

Leo was home.

Rosario is 300 kilometres by road from Buenos Aires. As you exit the motorway that cuts through a valley, you find a city of trees and skyscrapers. It’s a proud city. The Argentine flag was raised here for the first time. From these streets, decades later, came Che Guevara and Marcelo Bielsa and Cesar Luis Menotti. In his book, Messi, Guillem Balague spends five pages of Part 1 illustrating Rosario. Football is life here, he says. Home to the legendary Newell’s Old Boys team, and their fierce rivals, Rosario Central. Turn from any corner of a street, and you will find kids playing three-a-side games, murals painted over entire walls, jerseys hanging from windows and balconies, shops with scarves and memorabilia. When Balague went there, he found the city to be a shrine to the sport. Well, everything about the sport except one guy.

“You breathe football everywhere in Rosario, but curiously, the air doesn’t smell of Messi.”

Wright Thompson visited Rosario in 2012, when Messi was at the high peak of his career, and found bars with references to Keith Richards, Mick Jagger, and Rafael Nadal, but not their own. At some bars, the television operator chose cooking shows over the live broadcast of Messi’s Barcelona.

**

Lionel Messi was born into a family of Newell’s Old Boys devotees. For his first birthday, he was gifted a Newell’s kit. That shirt, one suspects, is still sitting in a drawer in one of the Messi houses, washed and ironed.

At three, his father, Jorge, gave him a football. The boy took it to bed that night and every night after, pressing the leather against his slender, bony torso. By seven, he was playing for a local club, Grandioli, running circles around other primary school kids. Newell’s Old Boys came knocking soon after. He joined a batch of other 1987-born kids in a youth team. They lost one game in four years.

In the meanwhile, his body betrayed him. At nine, he stopped growing. His parents drove him to doctors who explained hormones and deficiencies and daily injections that cost a fortune. Newell’s offered to help. Leo learnt to push needles into his own veins. He carried a small blue cooler to practice, hiding it behind the goal while he played. But, Newell’s were not rich, and had to eventually pause the support. Jorge Messi found someone who’d help.

On 17th September 2000, Leo and his family boarded a flight from Buenos Aires to Barcelona in complete secrecy. He was thirteen. FC Barcelona had seen some tapes, sent by Jorge Messi, and they were interested in giving the kid a shot. On their way out, the Messis told the doctor and the school principal. No one else. In Balague’s book, the introduction chapter is called “Where’s Leo?” His schoolmates thought he had hepatitis.

He left without a goodbye.

Youth teams and thirteen-year-olds don’t make headlines. The first sign of what they had lost would dawn on Rosario and Newell’s three years later, when this baby-faced, mop-haired 16-year-old was thrown into a Champions League game by Barcelona. On the pitch, surrounded by Ronaldinho and Samuel Eto’o, Xavi and Henrik Larsson, the boy looked a complete natural.

News about Lionel Messi travelled with the breeze, to every corner of the world. By the time Argentina truly got to know of him, he was already a star.

***

Leo had become Messi. Against Jose Mourinho’s body-slamming Chelsea on a muddy Stamford Bridge pitch; against Brazil at the FIFA Youth Championships; the hat-trick against Fabio Cannavaro and Casillas’ Real Madrid, especially the third goal where he left the Ballon d’Or-winning Italian defender grasping at thin air.

The contours of Messi’s football style were coming to light. He had this ability to slalom through defenders like an eel. Nobody could get near him; those who did couldn’t knock him off balance. The low centre of gravity gave him fluidity in the tightest corners. But, above everything, there was an innate romance with the ball. It spoke to him, listened to him. When he turned, the ball was velcroed to the inside of his foot; when he ran, it seemed tied to his toe. There was a bit of magic to Messi, a bit of…

April 18, 2007. Barcelona versus Getafe, a midweek cup tie under a glittering Camp Nou. 53,000 red-and-blue shirts in attendance. In the 28th minute, Messi received the ball on the right sideline of his own half. He jabbed the ball past the first defender, slipped it between the legs of the second, and took off, legs whirring, thirty yards of green swallowed in a blur. Near the penalty box, Messi took two touches - one inside, one forward - in what felt like a single twist of the body, trailing foot hovering over the grass, and wiggled past two more defenders. Now it was him versus the goalkeeper. Messi feinted to the right, leaving the ‘keeper ass-first on the floor, and chipped the ball with his right foot into the net.

This sequence was a carbon copy, down to the last shoulder drop, of what is known as the greatest goal of the 20th century. It was the final confirmation that Messi had a bit of him.

In 1928, Ricardo Lorenzo Rodríguez, better known by his pseudonym Borocotó, editor of the legendary Argentine sports magazine El Grafico, distilled the Argentine footballing spirit into a few lines. He described the “pibe”, the kid, as one with:

“… a dirty face, a mane of hair rebelling against the comb; with intelligent, roving, trickster and persuasive eyes and a sparkling gaze that seems to hint at a picaresque laugh that does not quite manage to form on his mouth, full of small teeth that might be worn down through eating yesterday’s bread… His knees covered with the scabs of wounds disinfected by fate; barefoot or with shoes whose holes in the toes suggest they have been made through too much shooting. His stance must be characteristic; it must seem as if he is dribbling with a rag ball. That is important: the ball cannot be any other. A rag ball and preferably bound by an old sock. If this monument is raised one day, there will be many of us who will take off our hat to it, as we do in church.”

As Jonathan Wilson says, El Pibe was a mischievous urchin, tough and skilful, who had learned the game on the streets. Borocotó’s sketch was, unknowingly, a perfect depiction of Diego Armando Maradona, thirty-two years before his birth.

Maradona was born in Villa Fiorito, a slum on the southern edge of Buenos Aires where the streets turned to mud when it rained and stayed that way for days. The sewage ran open. Kids played football with rolled-up socks because real balls cost money nobody had.

Poverty was Diego’s foundational truth. He played football to escape, but the more one saw him, everything about Maradona the person felt as if he never left Villa Fiorito. It was as if he was in a perpetual dogfight against injustice.

Diego gesticulated with every word, cried in public, called opponents things you’d be embarrassed to say in public. When he scored, he screamed. When he lost, he was inconsolable. In front of the mic, there was no filter between his heart and his mouth. When fame took him to the stratosphere, he lived like a man who believed every evening might be his last. Too much cocaine, too many women, too many nights that melted into mornings.

On Sundays, he was a god. El Dios. But, only on Sundays.

In 1984, at the height of his powers, when every elite European club wanted him, Maradona chose Naples. Naples was chaotic, passionate, struggling. It was considered a junkyard by the industrial north.

“I like to fight for a cause. And if it’s the cause of the poor, all the better,” Maradona said in his autobiography. He dragged Napoli to the Italian championship. Twice. He brought them European titles. The city painted murals of him with a halo. They named children after him.

Argentina beamed with pride. Between the 1870s and the 1920s, Argentina was a story of industry and prosperity. Immigrants came from far and wide, from Spain, Italy, and Central America, in hope for a better life. The highest population came from Naples. When Maradona wore the Napoli blue, it felt right, natural, a very Argentine union.

Then, of course, there was the England match at the 1986 World Cup. Maradona scored twice. One of them was, is, the subject of a scandal; the other one left everyone standing and dumbfounded. In Argentina, the first one, the infamous Hand of God goal, isn’t seen as cheating. It was viveza criolla, the clever trickery of the streets outsmarting the powerful. Four minutes later, when Maradona dribbled through six Englishmen to score the greatest goal the world had seen until then, it was a complete illustration of the Argentine spirit: we can beat you with our tricks, and we can beat you with our genius, and both come from the same place.

Argentina won two World Cups in that short time - 1978 and 1986. And yet, it is impossible to find references to the first. It’s almost as if the country wants to erase it from memory. At the time, Argentina was under a brutal military dictatorship. People were gagged, tied, sent to camps, killed, evaporated. An entire generation of young Argentines grew up looking over their shoulders.

That’s why 1986 means so much. It was catharsis for that generation, the moment of deliverance. And it was brought by El Dios.

It is crazy to think what Maradona achieved despite the environment he built around himself. The drugs, the Mafia connections, the abandoned children, the gun fired at reporters. And yet, Argentina loved him in full, with their whole heart. He was proof that someone could come from nothing, carry all that damage, make all those mistakes, and still rise to touch heaven with his left foot.

Maradona, wizardry and warts, was intensely Argentine, which is the only correct way of being an Argentine.

Messi, on the other hand, was a silhouette. He answered interviewers in single lines, only because single syllables would have been too rude. No outbursts, no tears, no rage. You could watch Messi for a decade and not know if he preferred wine or beer, sunrise or sunset, funk or folk. He barely even sung the Argentine national anthem before matches. He’d learned to be invisible everywhere except the pitch.

The Argentines have a term for this kind of reserve, this emotional distance that feels European: pecho frío. Cold chest. No heart.

At the 2010 FIFA World Cup, Argentina got the union of their dreams. Messi was the best footballer in the world, Maradona the national team coach. This was BB King and Eric Clapton coming together for an album. Maradona built his team around Messi. Every attacking move would have his footprints. This was meant to be Messi’s World Cup.

In five games, Messi didn’t score once. In the group stage, South Korea, Greece, and Nigeria sent three players to mark and bruise him. In the quarter-final, Germany needed two, at times one. Messi was a ghost in white and blue stripes for those ninety minutes. The final score was Germany 4, Argentina 0. A thrashing for the ages. Once again, Messi bowed his head and disappeared into the tunnel.

Back in Barcelona, surrounded by his friends and a genius coach, he became Superman again. In the Champions League semi-final, he dribbled past five Real Madrid defenders, some of them left sprawling on the turf, to score a match-sealing goal. He scored again in the final against Manchester United and was awarded the Player of The Match.

Weeks later, Messi came back to Argentina to play in the Copa America. Argentina hadn’t won this tournament since 1993. It’s one thing to not succeed at the World Cup, around all the European powerhouses. In a smaller group of two genuine heavyweights, not winning it for eighteen years was insane. This edition was at home, giving them a chance to exorcise some ghosts of the World Cup. In the quarter-finals, they met Uruguay in Rosario - Messi’s home patch.

The match was taut, cagey. Neither team could dominate or conjure a moment of magic. Two hours of football passed by without a winner. Argentina lost in the penalty shootout. The crowd couldn’t take it anymore. They let out a primal shriek of disapproval and started booing Messi, one wave of insults after another.

Pecho frío.

**

Lionel Messi grew up in a house at Estado de Israel in Rosario. House number 525. This is where he first laid his left foot on a football, where he dined out on his grandmother’s pasta, where he first met Antonella, aged nine. The Messis never sold the house. It sits there still, no inhabitants, maintained by workers while the family lives in expansive compounds on the city’s edges. They keep track, though. The house means too much.

Messi returns to Rosario every time football gives him a break. His speed dial has had the same names for decades - cousins, uncles, friends from Newell’s youth teams. He’s in touch with his old club, his childhood doctor, his school. When Spain tried to lure him as a teenager, offering citizenship and the famous red jersey, Leo and his father smirked off the idea.

The deeper you get into Messi’s life, the more words you read from Wright Thompson and Guillem Balague and Luca Caioli, the clearer it gets: Lionel Messi has only ever called one place home, and it’s the place that barely acknowledges he exists.

**

On the pitch, Messi was becoming impossible to define. In 2012, he scored 91 goals for club and country. Ninety-one. It feels like a typo even today. The best forwards average somewhere between 30 and 40 goals in their most bountiful seasons. The absolute elite - the ones who get statues built - might do it thrice in a lifetime. Maybe four times. Between 2008 and 2013, Messi’s per-season goal tally for Barcelona read: 38, 47, 53, 73, 60, 41. And it wasn’t just about goals in his name. Messi laid passes on the plate for everyone. Henry, Xavi, kids from Barcelona’s academy - everyone dined out at his buffet. He won the Ballon d’Or - the award for the best footballer on the planet - four times between 2009 and 2013. No one had ever won more than three.

Through all of football history, he had one peer for this level of output: Cristiano Ronaldo at Real Madrid, who was posting similar video game goal-tallies at the same time.

At the 2014 World Cup in Brazil, Argentina arrived with stars but played like men afraid of their own shadows. Coach Alejandro Sabella had imposed a risk-averse approach on the team, stifling all their creative instincts. They crawled through the group stage - a laboured win over Bosnia, a last-second Messi thunderbolt to beat Iran, more Messi magic against Nigeria. The knockouts were even worse: 1-0 against Belgium, 1-0 against Switzerland, penalties against the Netherlands after 120 scoreless minutes. Good teams win, and they won, but they were mounting a solid case for being the most unspectacular contenders for a World Cup.

They reached the final. Germany stood across from them, efficient as ever. If Argentina had adopted defensive solidity as a costume, Germany wore it like skin. Once the game started, they barely gave Messi more than a glimpse. They knew every angle he preferred, every feint in his repertoire. Through the evening, Messi got one or two chances which truly counted as chances. He couldn’t convert. Late in extra time, young Mario Götze chested the ball and volleyed it past Sergio Romero. Germany 1-0 Argentina.

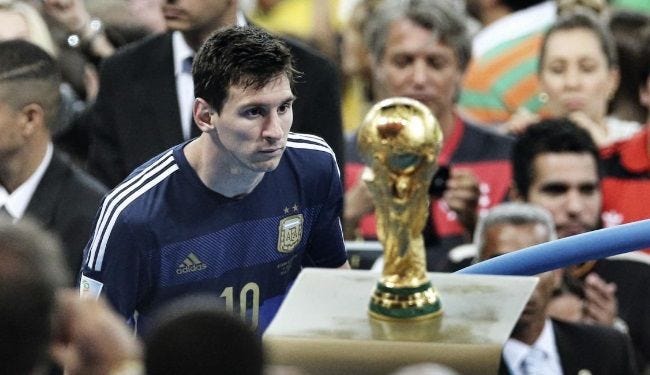

In a long and illustrious career, touching heights most athletes have not dreamt of, Messi has been in the centre of many memorable frames. Some of them are truly worthy of exhibitions and art galleries. And if there is ever a gallery of Messi pictures, it would contain that picture from the Maracanã. It was taken during the presentation ceremony. Messi, dazed, walking past the World Cup trophy after collecting his prize for Player of the Tournament, taking a wistful, split-second glance at the gold he couldn’t touch.

The following summer, in 2015, Argentina reached the Copa America final in Santiago. They faced hosts Chile. The match stretched beyond regular time, into extra time, then penalties. Messi scored his penalty, Higuain and Banega didn’t, Chile won.

The summer after, in 2016, Argentina reached the Copa America final in New Jersey. Chile again, extra time again, penalty shoot-out again. Messi missed his penalty this time; Chile won.

Three years, three finals, three versions of Messi that his own eyes wouldn’t recognise. Shots that should’ve nestled into the net landed in Row F. Free kicks bumped into human walls. Passes meant for teammates found the white chalk of the touchline. This couldn’t be the same man who turned football into ballet, who existed on a plane above his colleagues and peers. Somehow, every time he got close enough to touch gold, his feet turned to jelly.

The Argentines didn’t think his feet were an issue. It was his chest - that cold, European chest that couldn’t pump hot Argentine blood when they needed it most.

Pecho frío.

After the 2016 final, Messi broke down on the pitch. These weren’t tears of loss or hurt, but of something coming apart within him. “This is not for me. I am done,” he told the press in the mixed zone. He was just 29 at the time.

Argentina woke up the next morning to a throbbing national panic. The boy they’d rejected for years had suddenly rejected them back. Within hours, #NoTeVayasLeo exploded across social media. Kids filmed themselves crying, begging Messi to not leave. Grown men who’d booed him in stadiums posted videos apologising, kneeling at the gates of his old house. In Rosario, they hung banners. Half of Buenos Aires gathered around the Obelisk with Argentina flags and Messi tattoos on their arms. The president called him personally. Even Maradona, who’d spent years taking veiled shots at his successor, went on television to beg him not to quit.

It was as if Argentina had finally realised the depth of that old idiom: you don’t know what you have until it leaves you. They’d spent years asking Messi to prove he loved them. Now they had run out of time to prove they loved him back.

After a summer of soul-searching, Messi heard their plea. In August, six weeks from the night in New Jersey, he was back in the Argentina squad. He loved the shirt too much, he said, and didn’t want to add to the team’s problems.

But, this was a different Messi. Even for Barcelona, there was a sense that something had shifted within him. He got tattoos on his arms and calves. He fought with referees and jabbed at the press. The most docile man to ever play top-level football was chest-bumping opponents and taking red cards.

Argentina almost didn’t make it to the 2018 World Cup. Messi dragged them there. Then, they began their tournament by drawing with Iceland and losing 0-3 to Croatia. From the precipice of a first round exit, they somehow crawled back against Nigeria. Messi ran the show that afternoon.

They faced France next. A young, dynamic, sparkling France. Leading their line - a lean, lithe teenager, who ran like the wind. He’d become a superstar. That game, an instant classic, ended 4-3 to France. Argentina boarded the flight back across the Atlantic, but without the stench of an insipid display.

Beneath the disappointment, there was a foundation sturdy enough to build upon.

Lionel Scaloni was born in Pujato, about 20 miles from Rosario. He, too, began his career at Newell's Old Boys, as a defender who could fill-in for a midfielder. Around the same time a 7-year-old Leo was turning heads for Newell’s youth team, Scaloni was playing for the first team. An excellent utility player, Scaloni travelled to clubs in Spain, England, and Italy.

In 2006, he was part of Argentina’s squad in the World Cup. Many times, the combination play on the right wing involved overlaps and underlaps between Scaloni and a 19-year-old Messi. Argentina were one of the favourites in that World Cup, but they crashed out in the quarter-final. Scaloni knew all about the pressure and pain sewn into the Argentina kit.

In 2018, after the World Cup exit, Scaloni was made the national team coach. He was fresh. Unlike Sabella, he didn’t want to sit back and play without enterprise. And unlike Maradona, he didn’t think it was wise for every ball to land on Messi’s feet. The creativity had to be shared, and Messi had to be, for the first time in his career, liberated from the anxiety of carrying this team. So Scaloni built a midfield of muscle and grace, players who could rough you up and thread a needle with a pass. Ángel di María and Sergio Aguero led the line.

In 2021, Argentina reached the Copa America final again. They landed up at the Maracanã, with Brazil were waiting for them, surrounded by eighty thousand feral bodies wearing the canary yellow.

Messi had a quiet game, almost invisible. But Scaloni’s design had accounted for it. Others could carry the load. Ángel di María, freed from Messi’s shadow, dinked a delightful chip over the Brazilian goalie in the 22nd minute. The midfield bulldogs in white refused to break. Brazil pushed, Argentina held.

When the final whistle blew, Messi collapsed to his knees. He had his first major international trophy. Even the Brazilians clapped for him, unable to begrudge him this moment. That said, it wasn’t, still, catharsis. Just the prelude.

Scaloni and Messi set their sights on the ultimate gold figurine. It could be done, Messi told everyone. Argentina roared back in applause.

**

At the 2022 World Cup in Qatar, France, the defending champions, were the overwhelming favourites. Spain looked good. The bookies liked Brazil the most.

By this time, Messi had left Barcelona. After twenty-one years under the Catalan sun, his wages were too much burden for a financially hollow organisation. Pay cuts weren’t going to help. Years of poor recruitment and planning had left Barcelona on their knees. Messi cried at the press conference.

Back in Qatar, Argentina’s 36-match unbeaten streak, stretching back to 2019, had slipped under the radar. Messi, as always, was the subject of great attention, but not many considered Argentina strong enough to mount a title challenge. Then Argentina lost their opening game to Saudi Arabia. The memes were hilarious, Messi and Scaloni’s faces even more so, although everyone felt a bit sad for the team. They had built such great momentum, and yet again fluffed their lines under the bright lights.

They regained some balance to beat Mexico and Poland. Messi was landing a shimmy here, a pirouette there. He was beginning to find his groove. They went past Australia too. Messi scored.

Then came Netherlands in the quarter-final. Coached by Louis van Gaal, drilled to the last detail, hard to beat. In the 35th minute, Messi took the ball high on the pitch, and looked up to find seven defenders still between him and the goal. Worse still, just two teammates hidden between that dense orange forest.

It’s been nearly thirty months since. I keep thinking back to that moment. Messi is exceptional with long shots, so maybe it would’ve made sense to whack it from a distance. With the score still 0-0, a chance was worth taking. He also had a safer option, the pass to the left, where the wingback and another midfielder had ample space to control the ball.

Maybe that’s what the Dutch defenders thought too. Messi turned his body towards the left flank, creating the illusion of a harmless lateral pass, and then, like a longitudinal brush stroke on a canvas, his left leg sent the ball inwards, threading four defenders, finding Nahuel Molina one on one with the goalkeeper. 1-0.

It was a ridiculous pass, impossible to imagine or manifest, but so typically Messi. The kind of pass we had seen him float to Iniesta and Dani Alves for years.

Argentina vs Netherlands turned out to be one of the games of the tournament. The game went to extra-time, then penalty shoot-outs. I wonder if Messi thought back to all those Copa America nights as his team lined up at the centre-line.

Argentina won.

In the semi-final, they came up against another hard-drilled team in Croatia. On Messi’s side, the Croats posted Josko Gvardiol - 20-year-old, built like a tank, technically exceptional. Pep Guardiola’s Manchester City had been chasing him. Messi, looking every bit his best self, gave Gvardiol a public rinsing, turning him inside and out en route to setting up the third goal.

3-0. Argentina were in the final. But, now it wasn’t just about Messi’s dream anymore. A new generation of superstars had entered the conversation.

For instance, Kylian Mbappe. A lab-generated exocet for the 21st century. Mbappe didn’t know fear, just the scent of success and ambition. When he was a teenager at AS Monaco, his family had become his “team”, starting to mould PR strategies and comic books. At 16, he played in the Champions League; at 18, he scored in a World Cup final victory for France. Four years from that, Mbappe was fully formed into an impossibly gifted specimen, a superhuman footballer.

Argentina stormed to a 2-0 lead. The goals were scored by others, but the little touches of magic were applied by Messi. The midfield kept their promises. 81 minutes passed; nine to go. Messi’s lifelong dream of a starlit sky was within arm’s length now.

Mbappe scored one. Then, one minute later, he unleashed a volley while parallel to the ground, a goal that belongs to video games and five-a-side matches in a park. Mbappe pulled it off in a World Cup final to draw his team level.

Messi scored again. Mbappe scored again.

As the game drew to a close, with seconds to go, France’s Randal Kolo Muani was sent clean through on goal, one on one with goalkeeper Emiliano Martinez. The stadium went quiet the way stadiums do when everyone sees the same thing at once. It was going to happen again. Another random player was going to break Messi’s heart. The script was already written.

Martinez threw himself to his left. The ball hit his boot and spun wide. Messi stood fifty yards away, hands on his hips, heart still in his mouth.

Penalty shoot-out again. I wonder…actually, I am convinced Messi thought back to all those Copa America nights. The jeering, the tears, the feeling of being the best in the world yet inadequate. How could he not? The same bloody thing, over and over and over again. When was it going to stop? How had the most defensively solid team in the world let slip a 2-0 lead in a World Cup final?

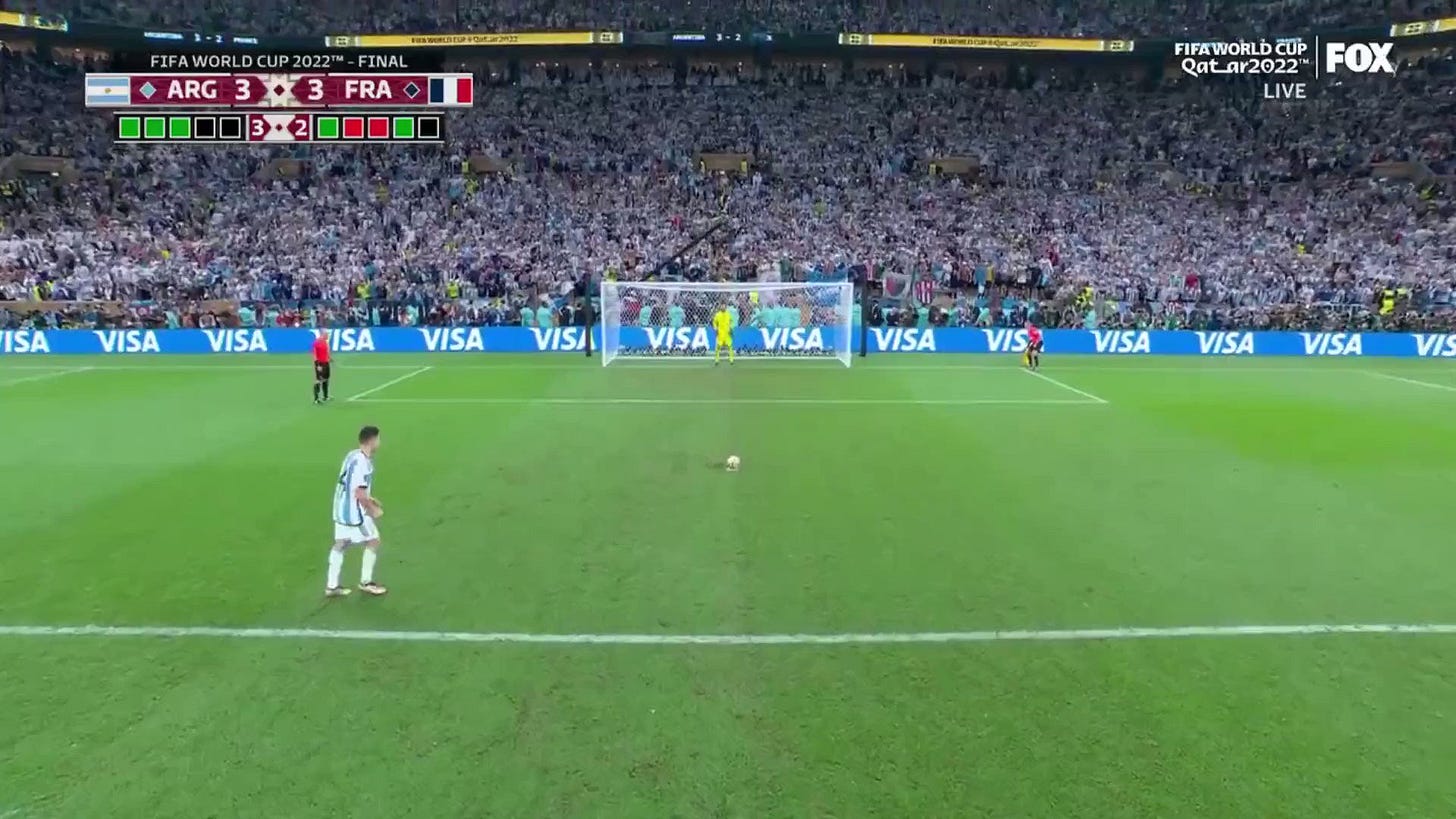

Mbappe scored. Messi scored. France missed their next two, Argentina scored theirs. Kolo Muani scored. Gonzalo Montiel walked up to the spot. Half of the Lusail Stadium, all of Argentina, closed their eyes.

Montiel sent the ball to his left; the goalkeeper went right.

For a second, nobody moved. Then Messi fell to his knees on the halfway line, hands covering his face. The dam had broken. At that point, Lionel Messi had scored more than 750 professional goals. He knew every harmonic frequency that a net creates when a ball hits the white mesh. Every harmonic frequency bar one. He finally heard it, from fifty yards distance, the sweet swoosh of a World Cup-winning goal.

His teammates ran toward him, piled on top of him, making a moving knot of blue and white. From the southernmost windswept tip of Ushuaia to sunny San Salvador, in the buzzing arteries of Buenos Aires and the leafy lanes of Rosario, an entire country burst into raptures.

Deliverance.

Born one year after Argentina’s last World Cup, Lionel Messi’s entire career had been about carrying what others couldn’t lift. He represented, proudly, a footballing nation that wins less than it should, that even in its own continent sometimes plays third fiddle to Brazil and Uruguay. He’d spent two decades with that weight wrapped around his ankles like chains.

**

On September 4th, 2025, in Buenos Aires, those banners weren’t asking for more. They just wanted to say thank you.

Messi has played most of Argentina’s games since the World Cup triumph. Scored, dribbled, been Messi. He’s led Argentina to another Copa America, just for some extra frosting on the cake.

But, last week, he was finally home.

One would understand if Messi wants to play a World Cup without the burden, to have the time of his life. And one would understand if Messi feels he has given everything there is to give. If he wants to untie the shoelaces.

“A man sets out to draw the world. As the years go by, he peoples a space with images of provinces, kingdoms, mountains, bays, ships, islands, fishes, rooms, instruments, stars, horses, and individuals. A short time before he dies, he discovers that the patient labyrinth of lines traces the features of his own face.” - Jorge Luis Borges, The Maker

An essay worthy of the subject. The level of detail and research is stunning.

So good. Your writing is like watching a thriller.