In Frames: South Africa's Long Walk Home

Ten photographs to walk through three decades of history

South Africa were one hit away from glory. Australia, being Australia, were making them sweat for every run. But the result was beyond doubt, even for the battle-hardened cynic. The podiums were getting decked up, speeches were being rehearsed. The camera crew, sensing the gravity of the occasion, hunted for faces, that held-breath look of a people waiting to exhale.

Graeme Smith, wearing the black suit and grey tie given to all broadcasters during the World Test Championship final, had walked down from the commentary box to be pitchside. His smile stretched nearly as wide as those famous shoulders. Up in commentary, Shaun Pollock couldn’t sit still anymore. AB de Villiers was in the Grand Stand, one arm around his son, the other holding up a phone. Dale Steyn was home, watching with misty eyes.

One could reel off names of South African cricket legends without missing a breath, but I wanted the camera to somehow find one more face: Jonty Rhodes. For my generation, and the one just before, Jonty was our introduction to South African cricket. It was a rich culture, a lineage that went from Aubrey Faulkner in the 1900s to Graeme Pollock in the 1960s, but they were taking their first steps back in the sunlight of international cricket after 21 years. How much could that culture preserve through two decades of darkness?

They alighted in Calcutta, my city, but the real homecoming - arms thrown wide, tears and all - happened a couple of months later at the World Cup in Australia.

Ten days into their campaign, Jonty Rhodes did this.

My favourite version of this picture is monochrome too, but it's a top-shot which shows Jonty at his most natural: a blur. South Africa had answered the culture preservation question in their tournament opener against Australia. Jonty’s dive sealed something else: they weren’t taking any tentative steps. Quite the opposite. They were coiled for a sprint, waiting for the starting gun.

Cricket was a batter and bowler’s game. The bowlers ran, the batters hit. Pace and power. Those who could do both were robed in 24-carat gold. Then Jonty arrived, inventing a third genre. He turned fielding into jazz - all improvisation and impossible angles. He flew, ran, slid, jumped, glided. Fielding was cricket at its most physically expressive, and no one had quite explored its range like this. One time, he was awarded the Player of The Match for his fielding alone. That's how good he was.

You had paid to watch Viv, Lillee, Marshall, Imran, Kapil. Now you paid to watch Jonty.

***

Apartheid is Afrikaans for ‘apartness’.

In 1948 Daniel François Malan's Herenigde Nasionale Party won the South African general elections. Malan was a man of evidently simple promises, and his entire campaign pivoted around one idea: apartheid and racial segregation.

The first apartheid law was the Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act, 1949, followed closely by the Immorality Amendment Act of 1950, which made it criminal for South African citizens to pursue relationships across colour. The Population Registration Act of 1950 sorted the South African people into four racial groups: "Black", "White", "Coloured", and "Indian".

Sport fell in line. Separate clubs, separate governing bodies. White organisations and white people monopolised the ecosystem.

On 18th August, 1964, the International Olympics Committee shut the door on South Africa’s participation in world sport, starting with the Tokyo Olympics that year. The government had failed - refused, rather - to denounce apartheid, and, in a post-war world, it was about as grave as a war crime.

The regime's most important political prisoners were sent to the infamous Robben Island prison, that wind-scoured rock where the Atlantic met the Indian Ocean, where the humane and compassionate were locked in matchbox-sized cells. In the summer of ‘69, under tremendous pressure from the UN on the living conditions of the prison, the South African government allowed the prisoners to organise competitive football within the prison compounds. And thus was born the Makana Football Association - Makana being the name of the Xhosa warrior-prophet who had been banished there by the British military in 1819 for fighting against colonialist powers. The football league set a precedent for other sports, and on January 30, 1972, the Robben Island Rugby Board was founded.

Amongst the audience watching and observing the glue-like power of sport was prisoner number 466/64, Nelson Mandela.

The CIA had assisted in hunting him down. A man with a law degree and a conscience was that dangerous. For nearly three decades, the government made him disappear. He was allowed one visitor per year, with thirty minutes on the clock. When his mother died in 1968, when his eldest son followed in a car wreck, he wasn’t allowed compassionate leave for funerals. The state couldn't risk the symbolism of Mandela in daylight.

After twenty-seven years of imprisonment, on 11 February 1990, at 4:14 in the afternoon, Nelson Mandela walked out of Victor Verster Prison, into a world where he was a mythical hero. Hundreds of supporters lined the street outside the prison, many of them waving the green, gold and black flags of the African National Congress (ANC).

It was the first brick falling from the wall of apartheid South Africa. Robben Island was shuttered within twelve months, reborn as a museum to what humans shouldn’t do to each other.

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) officially readmitted South Africa in July 1991. South Africa were then granted a place at the 1992 Summer Olympics and the 1992 Cricket World Cup. They were also given the hosting rights for the 1995 Rugby World Cup.

To this day, the South African rugby team is called the Springboks, after a laser-sharp antelope native to South Africa. A gold springbok is sewn into the chests of their green jerseys.

During the apartheid years, non-whites were completely excluded from the rugby administration and the national team. The golden springbok, thus, became a shorthand for oppression and exclusion. After Nelson Mandela came to power, the national sports council wanted to burn the jersey and the symbol. Mandela went the other way. Keep the jersey, keep the name, but make the Springboks visit black townships. The faultlines from fifty years don’t fill overnight.

The winter of 1995 reached its zenith at the boisterous Ellis Park Stadium in Johannesburg, when Mandela handed over the gleaming, golden Rugby Union World Cup trophy to captain Francois Pienaar.

**

The third most important man in South Africa at the time, possibly only behind Mandela and Pienaar, was Wessel Johannes Cronje, most popularly known as Hansie.

Hansie could bat. God damn, he could bat. Against Australia in 1994, chasing a tall total, he whacked Warne and McDermott; against India, in 1992, a 135 came from 400-something deliveries. Muttiah Muralitharan was carted in Sri Lanka, Dominic Cork was thwarted for an hour in England. And yet, for all these gifts, there didn’t seem to be an obvious defining skill, that sprinkle of stardust which turned the very good into royalty.

So he turned into the architect. At just 25, he was given the leadership of a team that had only known international cricket for two years. He was one of the younger members of the team, but the decision was unanimous. There was something about his face. It oozed authority but the kind where he’d walk through fire first, and then flip out a stopwatch, goading you to beat him.

Herschelle Gibbs last played under him in 2000 but still speaks like a convert. He says, “He [Hansie] was an inspiration. Everybody that played under him never questioned anything he wanted and never asked why. They'd run through a brick wall for him.”

His tactical brain hummed at the speed of sound. He’d declare early, dangle carrots, manufacture results from guaranteed draws. In limited overs cricket, he sacrificed specialists and filled his team with all-rounders when most teams could barely fit two. When coaching meant instructions on whiteboards, Hansie wore wireless headphones to a World Cup game, and hid them behind nude-coloured tape.

A country emerging from darkness needed someone who walked like tomorrow was certain. Hansie walked that way, talked that way, led that way.

Until he didn’t.

In late-1999, Delhi Police's Anti-Extortion Cell was conducting phone surveillance to identify possible suspects in an extortion case. One lead pointed to another, and in March 2000, the police began tapping the phone being used by a part-bookie part-associate, Sanjeev Chawla. They stumbled onto a conversation between Chawla and someone speaking in “chiseled English with a foreign accent”. There was no extortion in the air, but a discussion about catches and runs. The man on the other side was Hansie Cronje. The Delhi Police released the transcripts and charged Hansie with match-fixing.

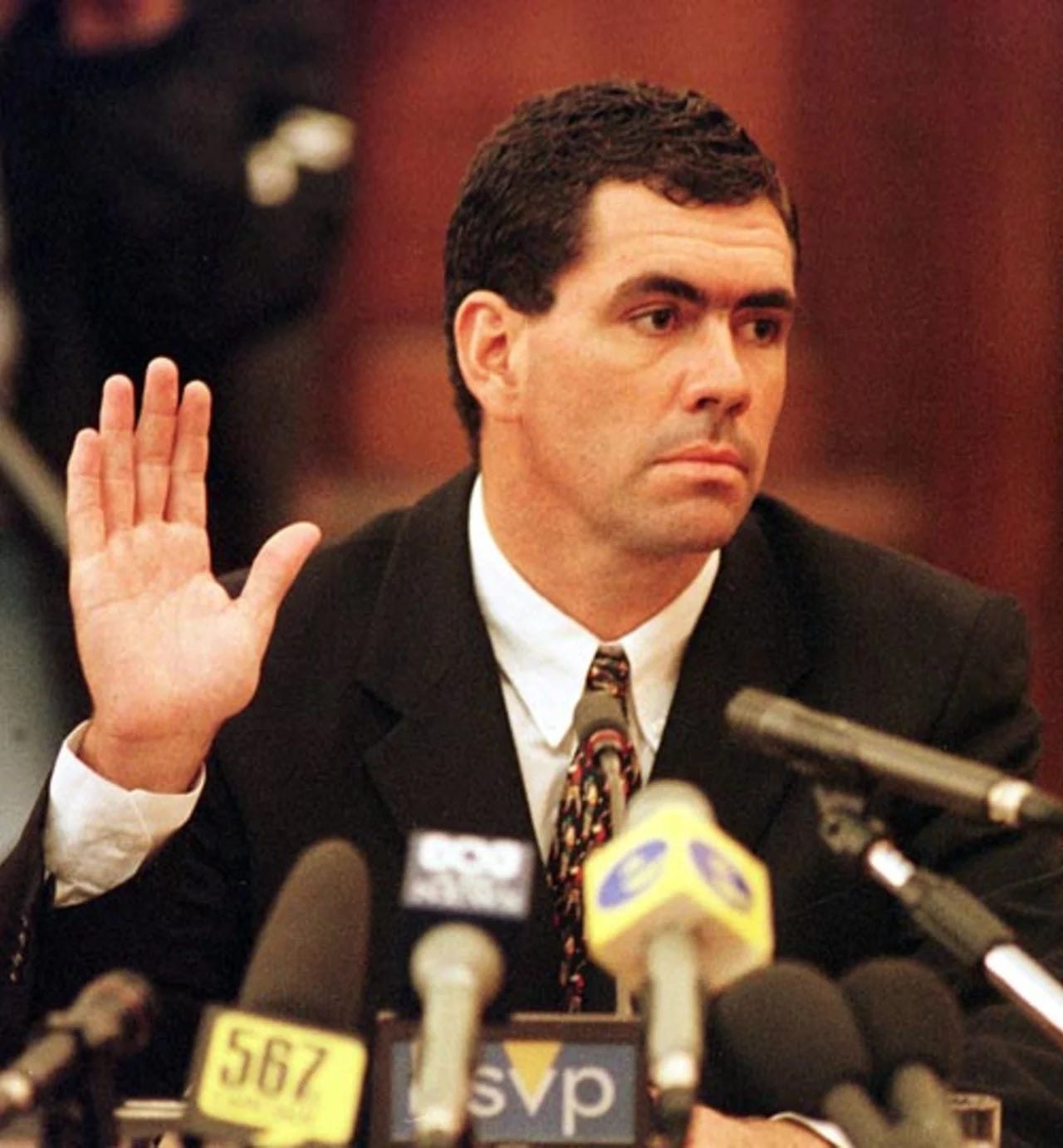

Hansie, dripping with the same authority that was his trademark at post-game interviews, denied any involvement. “I want to make it 100% clear that I deny ever receiving any sum of money during the one-day international series in India. I want to also make it absolutely clear I have never spoken to any member of the team about throwing a game.”

At the court, sitting in front of the King Commission, Pat Symcox fired the opening salvo, stretching Cronje’s corruption back to as far as the 1994-95 season. Herschelle Gibbs validated the noise by revealing that he had been offered $15,000 to throw a match. Henry Williams, Pieter Strydom, ditto. And then, Jacques Kallis, Mark Boucher, and Lance Klusener narrated a similar story.

After a three-day cross examination at the court, Hansie Cronje broke down in tears. An unfortunate love for money, he’d call it.

Two years later, almost to the day, Hansie was on board a light cargo flight, when it crashed into the Outeniqua Mountains. Dead at 32.

**

Jarrod Kimber - journalist, YouTuber, Instagram reeler, professional helmet wearer - nailed it in a recent video. Australia win most of the time, Zimbabwe lose most of the time. Everyone else floats in the middle. Everyone except South Africa.

I kept thinking about it because it is probably the most apt description of South African cricket through their second life. Over twenty-five of the last thirty years, South Africa have been the closest thing to Australia in cricket. For long stretches, even better.

But, unlike the rugby team, which has won four World Cups since readmission, their cricket team has walked a path of heartbreak and debris.

takes a deep breath Strap yourself in.

March, 1992: Remember the World Cup where Jonty Rhodes flew and South Africa announced themselves by beating the hosts, Australia? They breezed through the group stages and landed into the semi-finals against England at Sydney.

England batted first and scored 252. South Africa lost their first four wickets before reaching half their target, until Jonty and Hansie - yep - stabilised their innings. From needing 47 in 30 balls - gettable - they got to 22 from 13. Extremely gettable. And then the rain, which had been falling in a pitter-patter drizzle at the point, got heavy and the players had to go off.

Okay, some NASA-grade mathematics coming your way now. Here’s how the rain rule worked in those days. The rule was called Most Productive Overs (MPO), which essentially meant that when a match was curtailed due to rain - say a 45-over match was now 43 overs - the chasing side would have to chase the score set up in the most productive 43 overs of the side batting first.

The rain cost South Africa two overs. Now, they had bowled two maiden overs - zero runs - in the England innings. Two overs = 12 balls. So the target for South Africa, from 22 in 13 balls, went down to:

See, this is divine misfortune, right? What can you do? But this incident set into motion a pattern that felt heavier, more brutal, and painfully inevitable with every passing tournament.

April 1992: Their first Test match back. Chasing a mere 201 in the last innings, they reach 123 for two wickets. A stroll home. At the time, West Indies are the best team in the land, unbeaten in any Test series for twelve years. This being a one-off Test, South Africa have the golden chance to achieve something momentous in their first shot.

And then they lose their remaining eight wickets for twenty-five runs. Four to Walsh, four to Ambrose.

November 1993: South Africa are in the semi-finals of the Hero Cup. Calcutta is breathing a smoggy post-Diwali air. It’s chilly. South Africa are chasing, again. They need only 6 runs from the last over. India captain Mohammed Azharuddin throws the ball to a curly-haired teenager who’s actually a batter. What’s he doing bowling the last over of a semi-final?

Tendulkar bowls a smart over, Brian McMillan can’t connect with all his muscle-strength.

January 1994: South Africa reach the final of the tri-series in Australia. Comfortably the best team on show. They win the first of the three-legged final, lose the next two. Long flight home.

World Cup 1996: Twelve teams in the tournament, divided into two groups. South Africa are the only team to win all five of their group games. Noises emerging of them as an aux-favourite to land the trophy. They reach Karachi for the quarter-final against the West Indies, take one look at the pitch and go, “Nah, our best bowler can rest his feet. We need an extra spinner.”

Cue: Brian Lara slices them open. Long flight home.

January 1998: Scroll up, read the 1994 story, repeat.

World Cup 1999: Best team in the world. At the World Cup, they scythe through their group and second round. They’re guaranteed a spot in the semi-finals. In their last game of the second round, they face Australia at Leeds. Winner of that game takes the higher ranking into the semi-final.

No reconstruction of that week matches Rob Smyth’s epic, so I’ll try to keep it brief. At that point, South Africa had won 76 and lost 19 of all ODIs they had played since readmission. Absurd, ridiculous, whatever you want to call it. No one was even close. But there’s a catch: 6 of those defeats came in 17 games against Australia.

At Leeds, South Africa bat first and pile up runs. Then they have Australia in trouble. Steve Waugh does Steve Waugh things, gets to 56. Then he flicks one to Herschelle Gibbs’ palms, who gleefully accepts the gift, and just as he’s about to throw the ball up to celebrate, it slips from his hand. Reprieve.

Steve Waugh does more Steve Waugh things and guides Australia home. Absolute classic of a game, but four days later, there’s a rematch: the semi-final at Birmingham.

Australia bat first, South Africa bowl beautifully. 213 is a bit of a here-and-there total. Either way, South Africa start solid without any alarms. Just as they’re coasting, about to shift gears, Steve Waugh throws the ball to his best mate and full-time theatre artist, Shane Warne. Warne produces two deliveries out of the high heavens, bowls a spell that only he could, and drags Australia back into the game. Jacques Kallis resists, Jonty Rhodes resists, and South Africa breathe.

Enter Lance Klusener, the best player of the tournament by a mile and then some. He hacks and heaves South Africa to the doorstep of victory. 9 needed in 6 balls, the World Cup final beckoning from an arm’s length. But Australia are not done either; they need just one wicket. Damien Fleming bowls two near-perfect yorkers, Klusener dispatches both of them for boundaries. 1 required from 4 balls. The dressing room is in raptures.

Alright, done.

Yeah? Klusener panics, Donald - the man called White Lightning - freezes and forgets how to run, and Australia tie the game.

Remember the bit about the winner of the previous game taking the higher ranking into the semi? According to the rule book, the higher ranked team would go through in case of a tie. Australia go on to win the World Cup.

You think you know tragedy until you’ve known the air of Birmingham on 17th June, 1999.

Spring and summer, 2000: Hansie Cronje wins a Test series in India, and goes from the most identifiable captain in cricket to a match-fixer in two short months.

June 2002: Cronje, dead.

March, 2003: Home World Cup. South Africa start well, then flicker. It comes down to their final group game against Sri Lanka. They have to win. Rain, that familiar demon, shows up again, as if on cue. South Africa, can you believe it, are chasing again. But now, the rain rules have evolved to a complex mathematical formula devised by English statisticians, Frank Duckworth and Tony Lewis.

At the end of the 44th over, the South African dressing room sends a message that the score needed to be 229 by the end of the 45th, assuming no further wickets fell.

Mark Boucher smacks a six on the second-last ball. The score now 229, he safely defends the last ball of the over. They’d reached 229 and not lost a wicket. Mission accomplished.

But, wait. Do you hear that glitch, the white noise getting louder? The instructions had been wrong: 229 was needed for a tie. South Africa needed a win to go through.

World Cup 2007: Honestly, no chance against that Australia. They meet in the semi-finals, but the Aussies are too good. So good that Jacques Kallis, the picture of correct technique and composure, goes for an ugly charge at Glenn McGrath of all people and gets his stumps blown down.

World Cup 2015: Okay, they’re back. Kallis, Pollock, and Donald are long gone, but Steyn and Morkel are here, firing. Hashim Amla and AB de Villiers for the muscle, Faf du Plessis as the cushion, David Miller for the fireworks. Quite the unit. They cruise to the semi-finals.

At Auckland, they bat first, score heavily, and leave New Zealand a tall target. They aren't chasing, thank the lord. The Kiwis keep losing wickets, until Grant Elliott, born in South Africa, performs a rescue act.

12 needed off the last over, Dale Steyn to bowl. Steyn is one of the GOATs, he’s got this. It comes down to 5 off 2 balls. He’s got this. He runs in..

..and serves an absolute cookie. Fresh out of the oven, melt in the mouth kinds. Six.

ODI World Cup 2023: Semi-final, Australia, repeat. No heartbreak, but just can’t get past Australia. Australia win the World Cup (sigh).

T20 World Cup 2024: We’re nine-tenths through the final. South Africa are chasing, again. 24 needed off 24 balls. Heinrich Klaasen and David Miller are smoking the Indian bowlers to the roofs of the Kensington Oval. Even Jasprit Bumrah has only one over left. On commentary, Ian Bishop bellows, “Can the rainbow nation get its pot of gold tonight?”

At what point does a trend start becoming a curse? And when does that curse become an inheritance that younger generations have to carry?

The World Test Championship (WTC) final log sheet reads like a particularly unfortunate joke. South Africa are in England - the venue of their most brutal heartbreak. They're playing Australia - the team that caused them way too many heartbreaks. But, unlike other situations, South Africa are the overwhelming underdogs this time. It was widely suggested that the place in the gold medal match wasn’t deserved, but sneaked in through sheer luck.

After the first day and a half at Lord’s, the game felt like a mismatch on quality and pedigree. South Africa had bowled beautifully, but Australia had shot them out on day two. The Aussies - defending ODI world champions, defending WTC champions, holding every bilateral Test trophy - were now 100 ahead, looking to seal the Test match within three days.

Temba Bavuma, the South Africa captain, was calm as the sea on a bright morning. He always is.

In 2018, Siya Kolisi was made the captain of the Springboks, becoming their first ever black captain. He was already a superstar when he was given the top seat. The following year, he led South Africa to a World Cup title. Four years later, his Springbok team successfully defended that title.

Bavuma traced a different path. In 2022, he became South Africa’s first ever black Test captain, but it wasn’t a grand welcome to the throne. Many, even within the cricket ecosystem, argued that he shouldn’t even be in the team nevermind the leadership. He hadn’t scored a Test century for seven years. Turns out, he was a bloody good leader, and a top batter waiting for his moment. Under him, South Africa went on a winning streak and leapfrogged India to the WTC final.

So, here we are. South Africa vs Australia. South Africa are chasing, again.

They need 282 to win the final. No one had chased that many at Lord’s in twenty-one years. Only two teams, in history, have chased more. History, tradition, experience, skill, opposition - everything stares with ominous eyes at South Africa. They lose an early wicket; they lose their second not long after.

Temba Bavuma comes to bat. And it looks like it would take a bulldozer to get him out. He defends when the ball rises, hits when the ball is close. In the process, he gets a hamstring injury, starts limping, but refuses to leave the ground.

By the time he departs, to loud cheers across the most imperial symbol of Imperial England, South Africa are well in the driver’s seat. A position of advantage always counts for something, but not enough for South Africa. They have been here before. They know the smell of this seat, the feel of its skin, all too well. And they know how the ride ends.

Not today, not this one. When Kyle Verreynne hits Mitchell Starc for four, as Graeme Smith and AB de Villiers and Shaun Pollock leap in joy, as the player’s balcony explodes, Bavuma is glued to his chair. He puts his head down, letting the enormity of the moment, the occasion, and its significance wash over him.

Thirty-four years back, when South Africa played their first Test on return, there wasn’t a single black player in the team. Their first rugby team had one, just the one. It will take many more decades to erase the wounds from apartheid, but they now have pictures of triumphant dressing rooms with superstars from Pretoria, Johannesburg, Centurion, led by captains born in the distant townships of Langa and Zwide.

The rainbow nation have their pot of gold. It has taken them three decades to get here, but they could now say the five most beautiful cricket words: South Africa are World Champions.

Reading Recommendations:

More Than Just a Game by Chuck Korr and Marvin Close

Nelson Mandela and the Game That Made a Nation by John Carlin

This incredible essay by Firdose Moonda right after the WTC final.

This is a history lesson and a sports lesson. Epic writing!

Fabulous.