From Sunrise to Sunset

Just give Cheteshwar Pujara a bat and leave him alone

There is an image of Cheteshwar Pujara that has stayed with me for eight years now. It was late on a Sunday afternoon. Bangalore’s early-March heat had come in spurts - not quite biting, but insistent enough to turn cricket into an endurance sport. The shadows at the Chinnaswamy Stadium were sprawled across the field, languid like sleeping strays. The crowd, exhausted after a day that grew tighter by the hour, had begun to disperse.

Pujara had batted, unbeaten and flawless, for four and a half hours for his 79. One blocked ball after another, as four bowlers from a different hemisphere turned red and blue. Someone three rows behind me blurted, “He’s meditating or what?!” triggering a few chuckles around us. We were in awe.

As Pujara walked back to the pavilion for an evening’s rest, he could barely lift his heels from the ground. Nathan Lyon walked behind him, huffing and puffing, hands on his hips, shaking his head at Pujara’s retreating figure with the frustration of a bowler who’d thrown everything and still ended up short.

India won that game. Pujara would later admit to that innings as one of his best. In the next Test, two weeks later, he batted for eleven hours in the piercing heat of Ranchi to score 202.

Every run counts the same, but runs against Australia mean just a little bit more. You can rattle off generations of elite batters - Lara, Tendulkar, Kallis, Dravid, Inzamam, Sangakkara, AB, Kohli - and find Australia to be their most cherished target. Even in the second decade of the 21st century, as the green crest with two emus lost a bit of its dazzle, it still signified excellence and success.

Pujara scored nearly one-third of his career Test runs against Australia. Across three successive series wins - two on their turf - he was India’s spine. On that epic 2018-19 tour, he accumulated 521 runs, but, amazingly, endured 1258 deliveries, literally and metaphorically grinding the Australian bowlers to dust. No visiting batter has faced more deliveries in a Test series in Australia.

In the last Test of that series, as Pujara was piling up yet another century, Nathan Lyon couldn’t hold it in anymore. Not one for the ugly sledge, Lyon offered some words of exasperation: “Aren’t you bored yet?”

Two years later, he was back to haunt them. He kept an all-timer bowling attack at bay and shepherded a broken team as they mounted the most impossible, incredible series win.

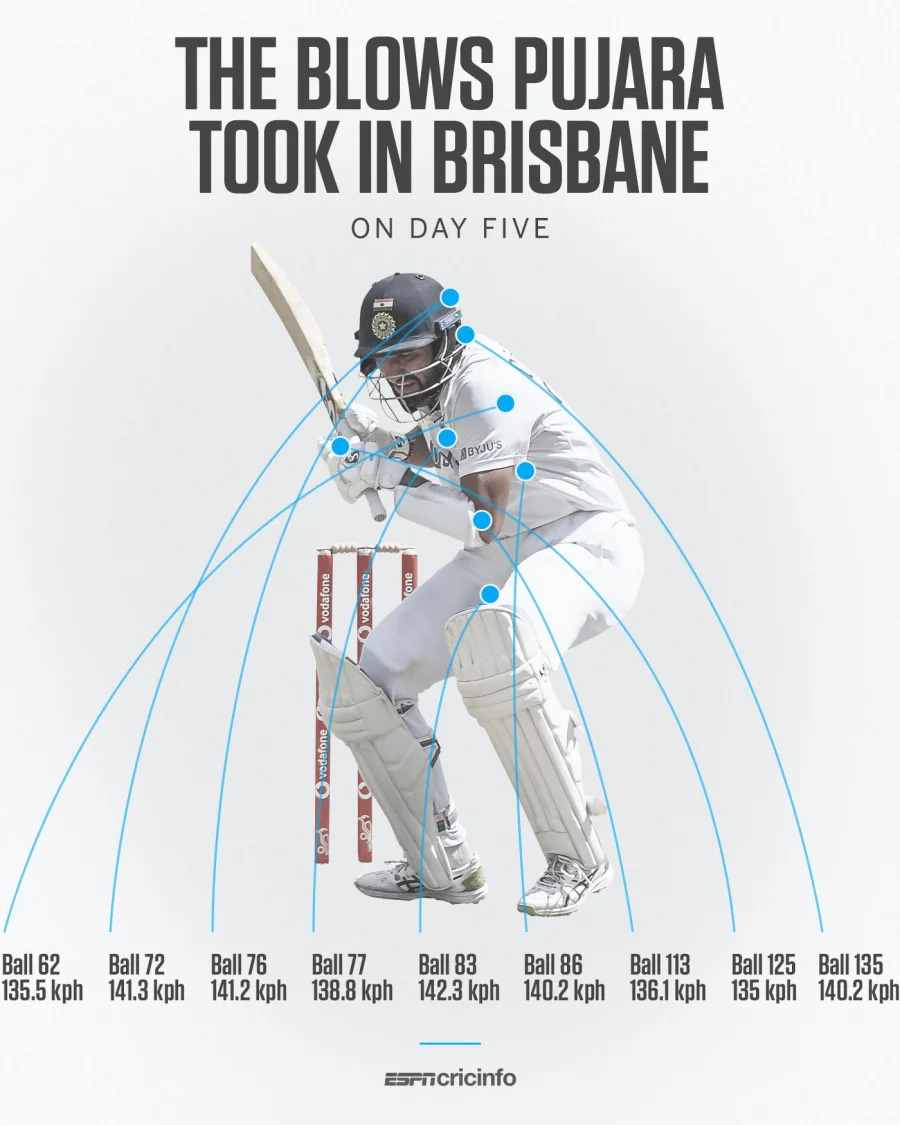

There is a famous infographic from the last of those knocks in Brisbane - a game he entered with a fractured finger. In the middle of the frame is Pujara, crouching as a ball thuds into his shoulder. Below him is the list of blows he took that morning, drawn like the morning-after graph of an artillery bombardment mission. His 56 became the bedrock of India’s final day miracle.

“There were a lot of body blows, but I was aware that the series was on the line. And I knew that if I can handle those body blows, at least for the first and second sessions, then our time will come.” - during an interview with Grace Hayden, here.

This past week, since Cheteshwar Pujara conveyed his goodbye through a social media post, his teammates have all lit a candle to his valour.

For thirteen years and a hundred Tests, Pujara was safety. He joined the team as a generation of greats began their descent. In time, he became the axis around which an exuberant new India leaped and soared. KL Rahul, Kohli, Rahane, Pant, Rohit - all have walked broader knowing Puji has their back.

When Rahul Dravid folded away his Test whites, the baton for number 3 was passed, without hesitation, to Pujara. It was both the highest honour and the heaviest burden. At Hyderabad, when Pujara strode out to bat as the anointed heir to the man they called The Wall, it was the culmination of one journey and the start of another. He scored 159 to mark the occasion.

Sandeep Dwivedi, who grew up in the same apartment complex as the Pujaras, tells the story of father Arvind and kiddo Cheteshwar.

“Ask any Kothi Compound resident of late 90s to early 2000 and they would remember seeing the Pujaras on most evenings in the corner of the Railways ground, under the neem tree, next to the volleyball court. The father rolling the ball along the ground, the son methodically bringing the bat down and playing it straight back to him.”

A few years back, Sid Monga hung out with them and found out about young Cheteshwar’s training routine.

“Cheteshwar's training was taken to the next level. He remembers having no days off. No Sunday. No festivals. Nothing. On days he went to school, he would wake at 5am, train at his father's camp, come back and finish homework, go to school from 12.30pm to 5pm - the afternoon shift allowing him to practise in the morning - rush back home and then back to the camp to make the most of whatever was left of daylight.”

Rajkot, for all its sleepy charm, could only take Cheteshwar so far. So, every summer, Arvind Pujara packed up his son and a kit bag and boarded the train to Mumbai.

“Every day, lugging the cricket kit in Mumbai local trains, father and son would head to some cricket ground or the other, hoping for match practice but never guaranteed it,” Monga narrates here. “In a good year Cheteshwar would manage three matches a week, which made it 18 matches on different kinds of pitches over the summer vacation.”

Pujara scored his first triple century at the age of 12. Over the next decade, as he leapt through age-levels and development programmes into senior teams, triple centuries became a bit of a theme. He scored three of those between 2008 and 2013. Every other week, the newspapers carried a story of Cheteshwar Pujara batting from sunrise to sunset. And these weren’t wanton whackathons against second-class bowlers; the runs came against the best in the country, on all kinds of pitches, invariably after hours of hard grind.

As you can tell, sweat became a consistent colour scheme on a Pujara canvas. Sitting at home and press boxes, we were smitten by his slow-burn, contemplative batting, his ability to not let any of 21st century’s excesses fall on him. And unfortunately, we confused the colour scheme for a watermark. We were unable to fully appreciate the range he brought as a batter, the talent he truly was.

Oh, Pujara could bat. As a doe-eyed 18-year-old, he top-scored at the under 19 World Cup. On his Test debut in Bangalore, against his favourites, he took India home with a breezy 72. In Hyderabad, opposite the Aussies once again, he bullied his way to a double-century, chopping through an inexperienced and admittedly-inadequate bowling attack. In Johannesburg, he went after Steyn, Philander, and Morkel. In Adelaide, after a flurry of wickets threatened to wreck India, he scored 50 runs in an hour with the tail.

Pujara didn’t possess the full range of shots as a T20-polished batter, but he had enough. He attacked based on necessity, using it for effect and not as a stylistic choice. Only after the ground was firm beneath his feet, or the scoreboard began to flash alarming numbers, would he allow himself a flourish, unleashing a wave of cuts, drives, and flicks. The shots still came with a certain minimalism instead of extravagance, like playing Eminem on the viola, but it moved all the right needles.

Speaking to Sid Monga about his batting philosophy, Pujara said, “When you defend confidently you know you are in command, you are on top of the bowler, and he doesn't have a chance to get you out. You will ultimately score runs when he bowls a loose ball.”

Cheteshwar Pujara craves control, wherever he is.

Puja Pujara, his wife, has recently published a charming book called The Diary of a Cricketer’s Wife. It’s part window into her own world, and part portrait gallery of Cheteshwar, rendered in affectionate, everyday detail. As their lives drift from city to city, hotel to hotel, we get to know Cheteshwar Pujara a little better. We get to know about his relationship with equilibrium.

In chapter fifteen, she recalls a hotel room conversation in Sydney.

“I’ve been dropped from the team,’ he announced. He seemed so indifferent. ‘I know,’ I said, equally stoic. He went silent for a bit and then remarked, ‘Our job is to put in the hard work and not think about the results.’ I kept quiet. He was taking refuge in the teachings of the Bhagavad Gita. If it helped him weather this storm, I was all for it. Over the next few hours, he reiterated this sentiment again and again. I looked on, troubled, not knowing how to reach out to him. He then spoke briefly to his spiritual guru. It was something he did before every match.”

Puja isn’t sold on her husband’s habit of bottling up his emotions - she says as much in the author’s note - but she’s come to understand how much he needs the scent of balance for his own sanity. She narrates stories of two ruptured knee ligaments and two heart-attacks - one for each parent. Through the falling and drying of tears, we get a glimpse into Cheteshwar’s capacity to absorb pain and setbacks.

The day his mum passed away, Che - affectionately called Chintu - was away for a cricket match. He came home to find the corridor packed with crying relatives. “I broke down, but not uncontrollably,” he told her. She adds, “However, as soon as he spotted his friends, he reassembled his face into a stoic mask and his tears evaporated, as if they had been wiped clean by an invisible hand.” Two weeks later, he scored a century against Gujarat.

While watching Pujara in the Indian whites, we didn’t always know of his inner life or mechanics, but we could sense the calmness he brought to the pitch. I think longform cricket gave him that space. He could be fully himself, bat like he always has, and build his repertoire on the thing he prized the most: defiance. Not defiance as mere self-preservation, but as a mode of aggression. Every series of dot balls was a tiny cut into the bowler’s psyche. Even as the weather around him changed, as Test cricket started to import exotic rhythms, Pujara kept sight of its ultimate batting truth: time is your friend. Five days is a long time, and bowlers are repulsed by serenity.

I sometimes think of his white-ball career and wonder if he ever felt cosy wearing those garish pop-colour clothes, or while having to devalue his wicket for short-term gains. He had the skills - he once scored a 61-ball T20 century for Saurashtra - but maybe never the taste for extravagance. From the days of the neem tree, Pujara has known batting to be a meditative exercise. A reverse scoop would’ve made his chest burn.

The timing of his retirement is poetic too. Just days later, news wafted in from the Caribbean that Kraigg Brathwaite - West Indies’ Test captain until March ‘25 - won’t be getting a central contract. Brathwaite, only 32 years old, has played 100 Test matches and zero T20s in his career. You read that right. No domestic leagues, no IPLs, no exhibitions - just absolute absence from his generation’s most popular party.

Pujara doesn’t prescribe that path. He told IndiaToday’s Rajdeep Sardesai that he “missed out, but wouldn’t recommend anyone else to make that choice.”

“Times are changing. The white-ball game is popular, and one needs to adapt to what lies ahead. If you are not a good white-ball player, then the chances of getting into the Test team are very limited. There might be exceptions—an exceptional player from the Ranji Trophy might be picked—but such cases are rare. I would recommend a young player to aim to play all three formats.”

Pujara sacrificed his limited-overs game, but without a whiff of regret. He’d rather chase stillness in a raging tempest. That’s why he rates those Bangalore and Ranchi knocks highly. He forced the world’s most potent bowling attack to run at him for hours and hours while he stood there as an unyielding monolith. This one time, on a minefield in South Africa, he took 54 balls to score his first run. He scored 50 runs and helped India to 187, enough to set the foundation for a memorable Test win. He calls it one of his best knocks in international cricket.

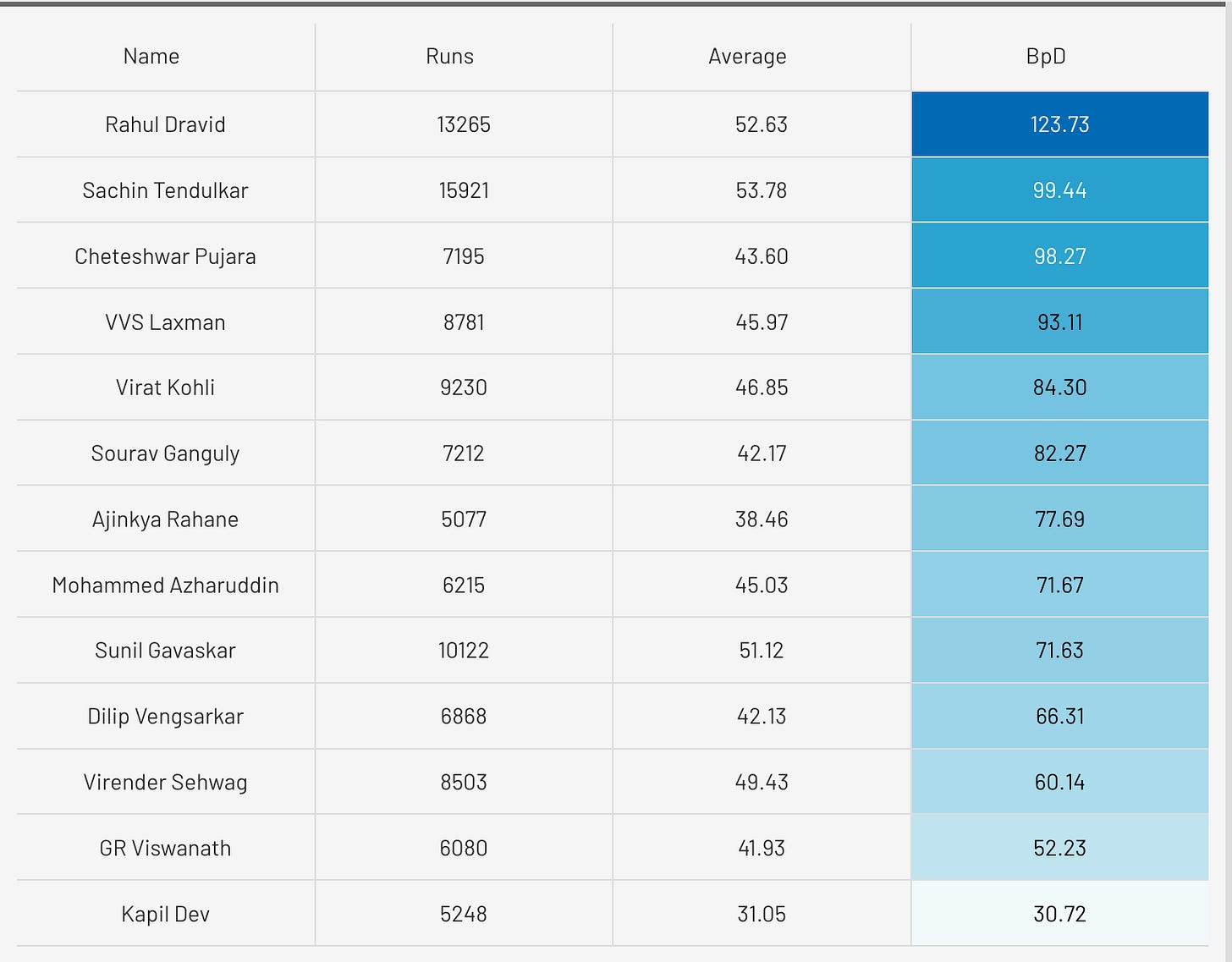

Cheteshwar Pujara leaves as a statistical dichotomy. His 7195 Test runs won’t make your eyes pop. He’s 8th on the Indian list, and will be eclipsed by more batters soon. But place the pivot on another column - balls per dismissal - to measure stubbornness. Pujara is third on that list, behind only Rahul Dravid and Sachin Tendulkar.

Cheteshwar Pujara was one of India’s finest.

Very well written Sarthak!

Sarthak, this is such a beautiful tribute to Pujara's quiet heroism. That image of him walking back from the Chinnaswamy with Lyon shaking his head in frustration - and then you weaving it through his entire career arc from those neem tree sessions to Brisbane - gives me chills.

What a player. What a tribute.