Counterpunch

It was coming

This is a clip from The Last Dance, a Netflix show about Michael Jordan, Chicago Bulls, and their epochal 1997-98 season. A modified version of this scene is now a popular meme, often used to depict instances where a slight provocation is met with an intense reaction. In the year 2020, a YouTuber stitched together a compilation of clips from the show where Jordan admits to taking seemingly inconsequential situations personally.

In one of them, Jordan describes an encounter with Bryon Russell, a 25-year-old rookie playing for Utah Jazz at the time. Russell had teased him, saying, “Why did you quit? You knew I could guard your ass.” Jordan's reaction gives us a peek into his psyche. “From that point on, he was on my list. If you're going to high-five, talk trash, I've got a bone to pick with you. I had to dominate this guy.”

At the point of Russell's dig, Jordan had already hung up his basketball shoes as one of the greatest of all time, and switched over to baseball. Despite all the records and titles, a minor taunt was enough to make him see red mist.

Just last week, after a dominant batting performance, Virat Kohli was given the mic to share his thoughts. His runs weren’t enough; he had a bit left to say.

“I am not quite sure if you've been in that situation yourself to sit and speak about the game from a box. I don't really think it's the same thing [as playing out there]. So for me, it's just about doing my job. People can talk about their own ideas and assumptions of the game, but those who have done it day in [and] day out know what's happening, and it's kind of a muscle memory for me now.”

In recent years, there has been a growing debate about Kohli's approach to T20 batting. He's an extraordinarily versatile batter, but the soaring tempo of T20 batting seems to be exposing a few uncomfortable gaps. This was his riposte to those debates.

And it wasn't even the first time this season that Kohli had taken a swipe at his critics. After the Royal Challengers Bengaluru's opening game, where he was named Player of The Match, he concluded his post-match interview with a cheeky, “I've still got it, I guess.”

People of his calibre don't like being questioned on their game. A writer questioning his strike-rate against spinners is like me, from my Substack, questioning the use of emotional devices in AR Rahman's music for Rockstar. (Side note: I hate it and genuinely believe that most of that music, barring Kun Faya Kun, is an overstimulation, like eating a Gulab Jamun dipped in Nutella. Good music, and indeed most of Rahman's incredible body of work, uses emotion-stirring cadences as an effect, not a recurring theme. It’s okay, I’ll stop. You can keep your guns down.)

I can understand why some might perceive Kohli's response as petulant. The role of a commentator or writer is to maintain a certain detachment from their subjects and view them as silhouettes while assessing their performance. There are very few who still subscribe to this philosophy, but those who do have every right to question a player without being asked about their own cricketing credentials. Perhaps there is a hint of defensiveness about Kohli's response, who knows?

But, if I'm being honest, I rather enjoyed the feisty tone. It tells me that he is willing to pick a fight.

Many other greats would've responded to questions about technical deficiencies with a polite smile. Some wouldn't even have bothered to react. But Kohli isn't Tendulkar or Dravid, and expecting him to wear their skin, even for a moment, would be both naive and wrong.

Kohli's reaction was natural to who he is.

Like any other city, Delhi too has multitudes, but you won't find laidback or relaxed amongst those shades. Perhaps it's the roughness of the weather, the overpopulated public spaces, and a generally tough bar to get past your competition, that keeps people on their toes. The person who helped you get onto a metro might snarl at you for accidentally bumping into them. At the nets of Ferozeshah Kotla or in the narrow lanes of Najafgarh, bowlers are more likely to greet a batter with a bouncer than a gentle loosener.

I know it sounds like a case of painting with a seriously broad brush, but in Delhi, you need to have a bit of an edge to cut past the crowd. Kohli has built his career on the foundation of an almost surreal work ethic, but he has always carried, proudly, the abrasions and combativeness that Delhi's air burned into his skin.

In 2018, days before India's Test series in Australia began, Cricket Australia posted a one-minute video of Kohli practicing in the nets behind the Adelaide Oval. It is an exhibition of sport turning into ambient music. Many commentators and ex-cricketers have called it a paean to modern batting. Tim Paine, Australian Test captain at the time, confessed to watching that video and exasperatedly asking his mother, “How are we going to get this bloke out?”

But if you listen closely, amidst the loud whips of his bat striking the ball, you can hear a voice. It is his, and he is constantly goading himself. After one slightly mistimed shot, he expresses his irritation: “Aaaaaah. Come on, Cheeks!”

Kohli cranks up this intensity by a few notches as soon as he crosses the boundary skirting. He wants hell to be unleashed on opponents and celebrates every wicket with the kind of energy one reserves for tournament-winning moments. He sometimes sledges bowlers when he's not even facing them. Last year, he unleashed this pearl: “Tere over mei 30 run maarunga, dalle!” (I will hit you for 30 runs in an over, you fucking pimp.) Which is, well, what a weird choice of a diss. Why pimp? But that's Virat Kohli: in your face, every ball, telling you in different ways when and how he's going to pin you on the mat.

Did we really expect this guy to listen to all those questions and criticisms, and respond with anything less than a counterpunch? And in his defence, it's a quirk shared by most all-time greats. They don't get to such giddy heights without believing in their infallibility. Critics provide them with a target to aim at, a subject to spar with. Sachin Tendulkar has entire chapters in his autobiography about how he took special pleasure in responding to his critics with the bat. The more you read and hear from their kind, the more you understand about the mental fortresses they build for themselves. No opponent is too daunting, and no mountain too steep. They invariably perceive any suggestion of a weakness, especially from outside their circle, as a personal attack.

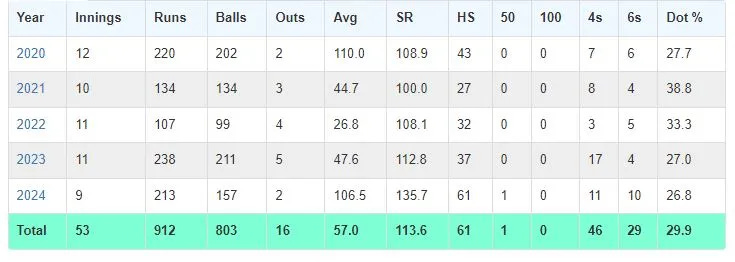

However, this doesn't mean that the mountain is a mirage. The questions raised about Kohli's T20 batting - to be specific, his strike-rate against spinners after the powerplay - are entirely legitimate. In this IPL season alone, he's at the top of the run-scoring charts, but is the fifth-slowest amongst the top 20 run-scorers.

Despite the national-level resistance to as much as raising an eyebrow at Virat Kohli, many are willing to dive into the data and fill the surface-level information with context. This lovely analytical piece washed up on my timeline yesterday. I will let Kashish talk to you about the oddity in Kohli's otherwise robust armour, but I'd like to share a chart from his essay.

To demystify the term - a strike-rate of 100 means one run per ball. One over has six balls, so a strike-rate of 120 would mean 7.2 runs an over. Similarly, a strike-rate of 150 would mean 9 runs an over. For the last few years, with shrinking boundaries and batters becoming increasingly powerful and imaginative, anything below 8.5-9 runs an over tends to put undue pressure on the rest of the team. Especially when a batter is so good that they often play long. Unlike in basketball or football, where points and goals always benefit a team, in limited overs cricket, runs need to be scored at a certain pace to begin helping a team's cause.

Consider, for a moment, the 16th of March, 2012, a red-letter day in cricket history. That afternoon, Sachin Tendulkar pitched his flag on the insurmountable peak of 100 international centuries. Just writing about it makes me feel dizzy. But what happened in the game? Few of us asked, even fewer cared. From the moment Tendulkar took off his helmet and raised his bat, the result got relegated to a footnote in microscopic font. Well, I am here to become Captain Buzzkill. Bangladesh chased the total down with minimum fuss. There is a case to be made, fairly so, that Tendulkar's inability to accelerate as the innings went long cost India a few runs, and eventually, the game.

The conclusions we draw from a scorecard depends on how much of it we choose to look at. In an ideal world, the result takes priority over individual scores, but who are we kidding with those utopian dreams?

There is a reasonable explanation for Kohli's batting style. He belongs to a generation, possibly the last, raised on the baroque principles of batting: play with the correct technique, and never surrender your wicket cheaply. Test and ODI cricket, where technique and defence hold high value, were the dominant formats when Kohli and his peers were making their way through age-group teams in their cities.

Since then, especially since T20s have gone mainstream and turned most aspects of conventional batting wisdom into Victorian gibberish written on dusty, crumbling paper, most have had to deal with a fork in the road. Some have adapted their style to become indiscriminate hitters; some rare ones, like AB de Villiers, seem to have been born with the ability to switch lanes at will; and some, like Kohli, have stuck to their side and refused to get swept away into this ideologically younger way of life.

Over the last decade and a half, four batters have established themselves as the most skilled technicians of their generation: Kohli, Steve Smith, Kane Williamson, and Joe Root. All of them have similar, risk-averse approaches to batting. Smith and Root will not even be playing at the T20 World Cup this summer, despite being automatic selections in other formats. Kohli, instead, will arrive in the USA as one of the favourites to go big.

I’m not sure if Kohli sees his middle-overs strike rate as a problem. Obsessive that he is, if he saw it as a glitch, he would’ve been ready to walk on hot coals to rectify it. And it doesn’t help that he represents an organisation and a fanbase that tends to deify its star players.

It would be so delicious if a journalist were to write an absolute stinker about him in The New York Times on the eve of the T20 World Cup. Kohli thrives on the big stage, and a piece like that will go down as a molotov cocktail into his bubble. After all this fuss, so many articles, maybe there’s a 30-ball century waiting to burst out of him. If that means a World Cup title and twenty such who-the-boss-now interviews, maybe some peppered with Delhi’s favourite expletive, I will drink to that.

A lot of ground to cover but this was so good. I wonder how the World Cup went. I love your writing Sarthak. I love everything you do on your sub.

Kohli is an all-time great obviously, and when he's done with his playing days there will be few records left standing.

The verbal retorts, mostly against reporters or lesser opponents, have a sense of punching down. Maybe it adds to his fuel, it doesn't change the nature of what he does.