At the End of the Tether

How long can a rope go?

The sound pierced through the stump mic. First, the hollow thud of glove hitting wood, then a primal scream that came from somewhere deep within the body. In the long walk back to the away dressing room at the Sydney Cricket Ground, Virat Kohli’s lips moved in a private conversation of expletives, all directed inward. The world beyond his personal maelstrom might as well have ceased to exist.

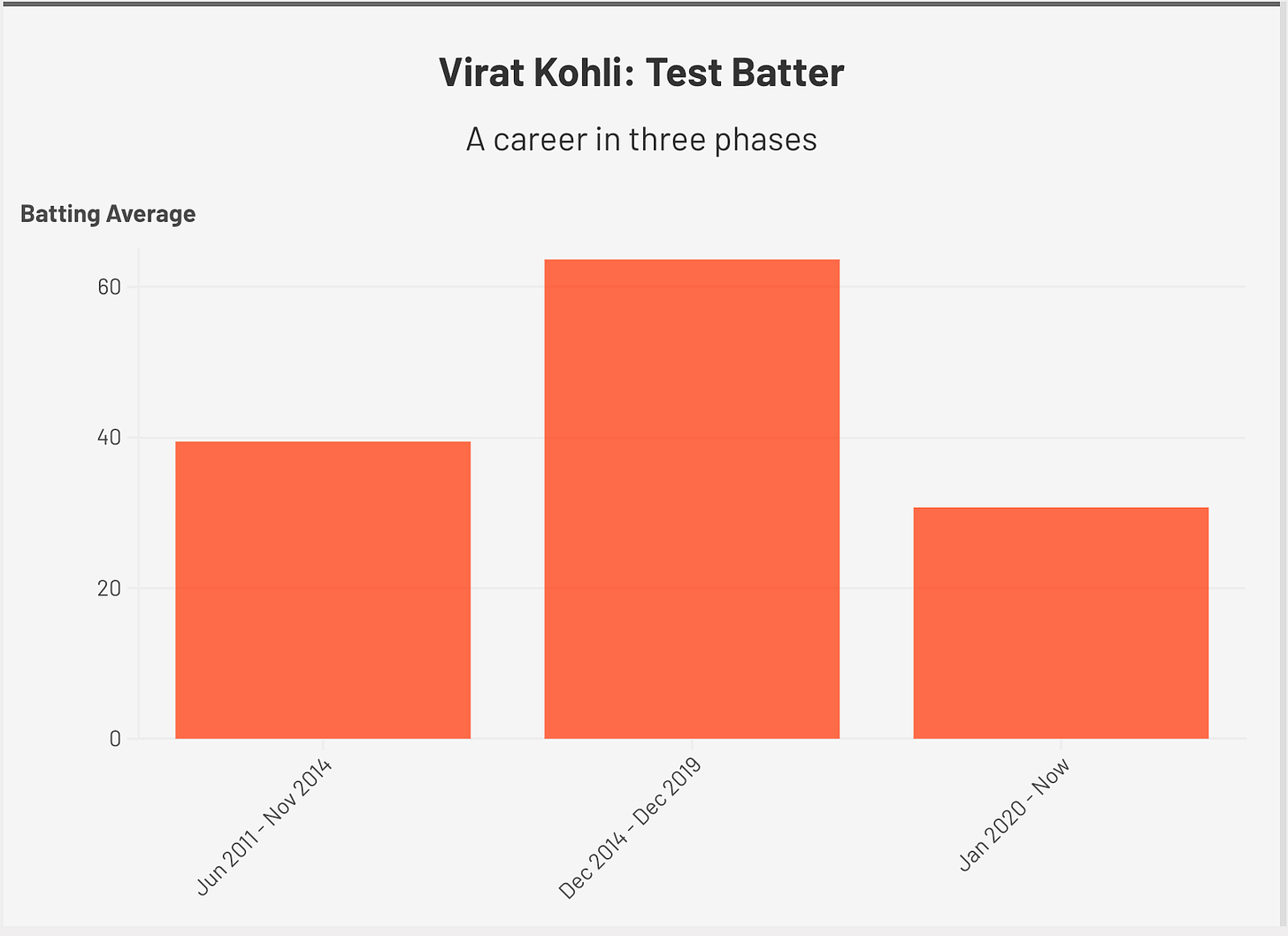

Kohli knows. This is no ordinary slump. This is an abyss that stretches back to those innocent days when Corona was just something you’d find in a beach bar, served with a slice of lime. The numbers speak their own truth, and they have developed a rather loud voice lately, but what Kohli has truly lost is the air of a king. His dismissals no longer shock; they merely confirm. Sydney was the latest episode in a long show.

Vulnerability hangs awkwardly on Virat Kohli, like an ill-fitted suit.

For a long time, he was the symbol of a confident India. In fact, he had emerged as the very embodiment of an entitled India, one that strode onto the world with shoulders thrown back and chin tilted skyward. This India did not only aspire for success, but expected it.

He made his name through ODI cricket, but had eyes for something greater - the most ancient, prestigious format of the game. Kohli loved Test cricket, and Test cricket learnt to love him back. After a rocky start, he grew rapidly from a talented youngster to someone who sat with Sachin Tendulkar on the royal front table of Indian batting. There were days, like in Perth 2018, when his first shot would convince everyone watching that a century is inevitable.

And when the waters got rough, as they inevitably do, Kohli found his way back through sheer force of will. In 2014, three months after enduring a hellish tour of England, he went to Australia, was thrust into captaincy, and reeled off four centuries in four Test matches.

To watch him enter a cricket ground was to witness royalty in motion - not the ceremonial kind that waves from balconies, but the sort that conquers territories. They say some athletes are forces of nature; with Kohli, even that description felt somehow insufficient, like trying to capture a thunderstorm in a photograph.

His captaincy mirrored his batting - built on absolute conviction and an unwavering faith in both people and possibilities. Ravichandran Ashwin tells a story from 2015, when Kohli had just become full-time Test captain. In a hotel room conversation that would prove prophetic, Kohli declared that bowlers would be the architects of his Test team's destiny. For the next six years, Kohli consistently chose attacking bowling options over batting insurance, and India's Test cricket bloomed like never before. Kohli remains India’s most successful Test captain of all time.

But, time’s shadow falls on everyone. Those golden skies are long gone. Kohli has not been captain for three years now, and, truth be told, he has not been much of a Test batter either.

Which brings us here, staring at numbers that look so jarring and yet won’t go away from the screen. Worse, every time we click refresh, the line on the graph seems to plunge a little more. Like Prem Panicker said in this wonderful article, “This is not a dip in form so much as a yawning chasm that points to the law of diminishing marginal returns.”

By the time Virat Kohli disappeared behind the glass door at Sydney, I wondered if he should play India’s next Test match. And I wasn’t the only one. Ricky Ponting and Ravi Shastri were already being asked about his “future” on official broadcasts. The digital media, once drunk on his aura, has been forced to acknowledge the full-sized elephant plonked inside a studio apartment in a cramped neighbourhood: Kohli isn’t contributing to the team with the bat. And unfortunately, stump-mic compilations and yelling at opponents doesn’t help win matches. Who knew?

The selectors find themselves in an unenviable position, tasked with humanising a deity of Indian cricket. This is a man who still commands a dedicated camera following him at grounds; who, recently, convinced half a country that it is okay to barge into a 19-year-old debutant on a cricket field; who, for a small while last week, was the stand-in captain and had all of us on tenterhooks. The runs may have evaporated, but the energy around Kohli has not.

I can’t help but feel sympathy for the tightrope Ajit Agarkar and team have to walk on, when they decide on the Test team and Virat Kohli’s future.

Consider, firstly, the backlash.

On the afternoon of 13th July 1998, hours before the FIFA World Cup final, Brazilian superstar Ronaldo began convulsing from seizures. He had been the tournament’s best player and Brazil’s one big hope of landing their second consecutive World Cup crown. He was so good that, a day before the final, the French defenders were gushing about his dribbling and technique. And suddenly, there were paramedics in his room, trying to resuscitate him, with half the team already packing for the team bus.

Coach Mario Zagallo - a World Cup winner as player and coach himself - left the decision until thirty minutes before the game. If Ronaldo could walk, nevermind run, he would start. Zagallo couldn’t take the risk of benching the team’s biggest star at a World Cup final. If Brazil lost - and France were bloody good - the backlash would be nuclear.

Ronaldo wandered through those ninety minutes in Paris like a ghost in canary yellow, each passing moment making the decision look worse. Yet, Zagallo's choice came from a place of pragmatism that sometimes triumphs over competitive sport’s cold logic.

Can one truly blame Ajit Agarkar if he hesitates before taking a decisive, bold call? The streets and social media would turn into amphitheaters of outrage. Television anchors would pronounce judgment with characteristic hyperbole. The Prime Minister will tweet about his sadness at seeing India dip further on the Global Hunger Index Kohli get dropped.

“Thing is, when it comes to the big players, we as a country are just not able to stay rational. Emotions run high and those in positions to take decisions on these players are influenced by this climate. Cricketing logic goes out of the window and then the selectors hope the player leaves on his own so that they don’t look like the villains who brutally ended the career of a great who millions of fans worship.” - Sanjay Manjrekar, for Hindustan Times.

There is a reason Indian selectors have always been meek when dealing with their biggest stars. This time, their job is further complicated by the transitioning Test team. Ravichandran Ashwin has just retired, Mohammed Shami doesn’t have too long left in those already-battered knees, and this entire article is applicable for Rohit Sharma too. Out of all of them, Kohli still has the most fight left, enough potential for a plausible mentoring role in a young dressing room.

Traditionally, incumbents have been identified through first-class cricket or shorter formats of international cricket. By the time Kohli made his Test debut, he had already scored five centuries in ODI cricket. He was marked out as the next in line. Right now, young talents like Sai Sudharshan and Dhruv Jurel are knocking on Test cricket’s door, but they aren’t yet fixtures in the international setup.

Secondly, taking Virat Kohli’s spot in the team, while he is still vying for it, is a poisoned chalice. It would take more than mere talent to weather the storm of comparison, to bear the chants and jeers that would inevitably be hurled at them. When MS Dhoni made way for Rishabh Pant, it took Indian crowds about an year before they stopped heckling Pant with chants of, “Dhoni, Dhoni” every time the ball came at him.

It helped that Pant was scoring overseas hundreds in his first year in Test cricket. Anyone replacing Kohli will have to start on a similar high note because they wouldn’t get the time to build into their career. Sport offers little time for apprenticeship when you’re replacing royalty. Fans will use every failure - and cricket is a game of failures - to scream into the void about the fraudulence of this young kid while their fallen king sells tyres on television.

There is, however, a bit of a refuge. One of cricket’s unique traits is that within the same sport, there are different formats, and different formats bring different playing conditions, equipment, and rules. Test cricket is almost unrecognisable from ODI (50 overs) and T20 (20 overs).

India don’t play Test cricket for another six months. In this time, they play a home ODI series and then the ICC Champions Trophy (also in ODI format), before the players disperse for the Indian Premier League (T20).

For Kohli, this schedule appears like an oasis in the desert. If Test cricket is his true love, ODI cricket is his most loving companion. He could sleepwalk into an ODI tournament and reel off a set of tall scores. Runs, average, centuries - his numbers are so insane, they could be called absurd. In the last ODI World Cup, held in October-November 2023, Kohli scored 765 runs in 11 matches. He isn’t just great, he is the benchmark, the gold standard, cricket’s finest craftsman of 50-over batting.

And look, six months can reshape narratives. A triumphant Champions Trophy campaign, followed by a strong IPL season, could alter the conversation entirely. At the highest level, the game becomes a little more mental than mechanical. For all his technical issues - there seem to be plenty - Kohli arriving in England, refuelled with a few gallons of ODI and T20 runs, might yet get to write his final chapter/s in bold-ish ink.

But, what if he doesn’t? It’s not just a possibility, but the more likely outcome.

The word ‘drop’ should live naturally in sport’s vocabulary. It should be a normalised part of a team game, where bad form can result in temporary benching or dropping. But in most sports, ‘drop’ carries the weight of a pejorative. Greats are given automatic immunity from clinical analysis, nevermind dropping or benching. They are instead given long, unquestioned runs.

Part of that comes from blind faith in their muscle memory, the other part comes from fear. With Kohli, a drop might get taken as an insult, possibly triggering a retirement. Like Manjrekar said in that article, no selector in this country would want to bear the burden of nudging out an all-timer. No one had the gall to question Tendulkar or Kapil either.

Perhaps our hesitation also reflects a deeper human truth - a fear of closing doors, of letting go. What if something precious is lost forever? And what if the next thing is not nearly as good? When comets of such brilliance streak across the night sky, you don’t know if and when you’re going to see the next one.

Kohli leaving cricket through force instead of choice is a scary thought, but a drop isn’t scary anymore. Even if it feels like those from the outside are passing a harsh judgement on someone still trying their best, even if there are flickers of good rhythm visible through a generally dense fog, the conversation about his place in the Test team is imperative.

He will and should start the England Test series in July, but hopefully with the understanding that he is at the end of the rope.

**

Virat Kohli’s aura peaked with a one-minute YouTube video.

On 4th December 2018, one day before the start of that year’s Border Gavaskar Trophy, Cricket Australia released a YouTube video of Kohli batting in the nets behind the Western Stand of the Adelaide Oval. Clothed in black-and-orange training gear, Kohli marks a leg-stump guard with four brisk scratches and gets to work.

A clever cameraperson, crouched behind him, shot the entire training session, which was then edited into a clip for digital media. They had inadvertently captured lightning in a bottle. Within twenty-four hours, that clip was watched some three million times.

Gideon Haigh described the soundtrack as “a succession of improbably deep detonations from Kohli’s bat, echoing off the stand’s bricks like a skeet-shooting rifle.” In an article for The Times, Michael Atherton called it a paean to modern batsmanship. Australia Test captain Tim Paine confessed to watching it, getting spooked, and asking his mum, “How are we ever going to get this bloke out?”

Six years and a bit hence, when Kohli landed in Australia for the latest instalment of the Border Gavaskar Trophy, the mystery around his dismissal had evolved from enigma to common knowledge. Scott Boland, with the matter-of-factness of someone sharing a recipe, detailed to the press the exact coordinates of Kohli’s vulnerability. Cue: nine innings played, eight dismissals in a similar manner.

I am not sure if there’s a deeper trough that a batter of his stature can touch, but I don’t necessarily want to know. At some point, the statistical gymnastics - the twenty-five filters we apply to make the numbers more palatable and a little kind - become exercises in collective denial. We’re simply bargaining with reality, unable to accept that our emperor of batting now stands in threadbare clothing.

There is a logical case to be made for extending a line of credit to those deserving of it, but a time comes beyond which they turn into liabilities. Kohli may not be a liability to the Test team right now, but there isn’t a lot of distance left before he turns into one.

Only here to say that "trying to capture a thunderstorm in a photograph" made me go, Bloody hell, how tf does he do this everytime - which, I suppose, is what a lot of people (used to?) say about Kohli's batting.

Hate you for saying it. Especially the last line. Would like to counter with “shut up and get lost.”