A Minute's Silence

On Diogo Jota and a George Orwell essay

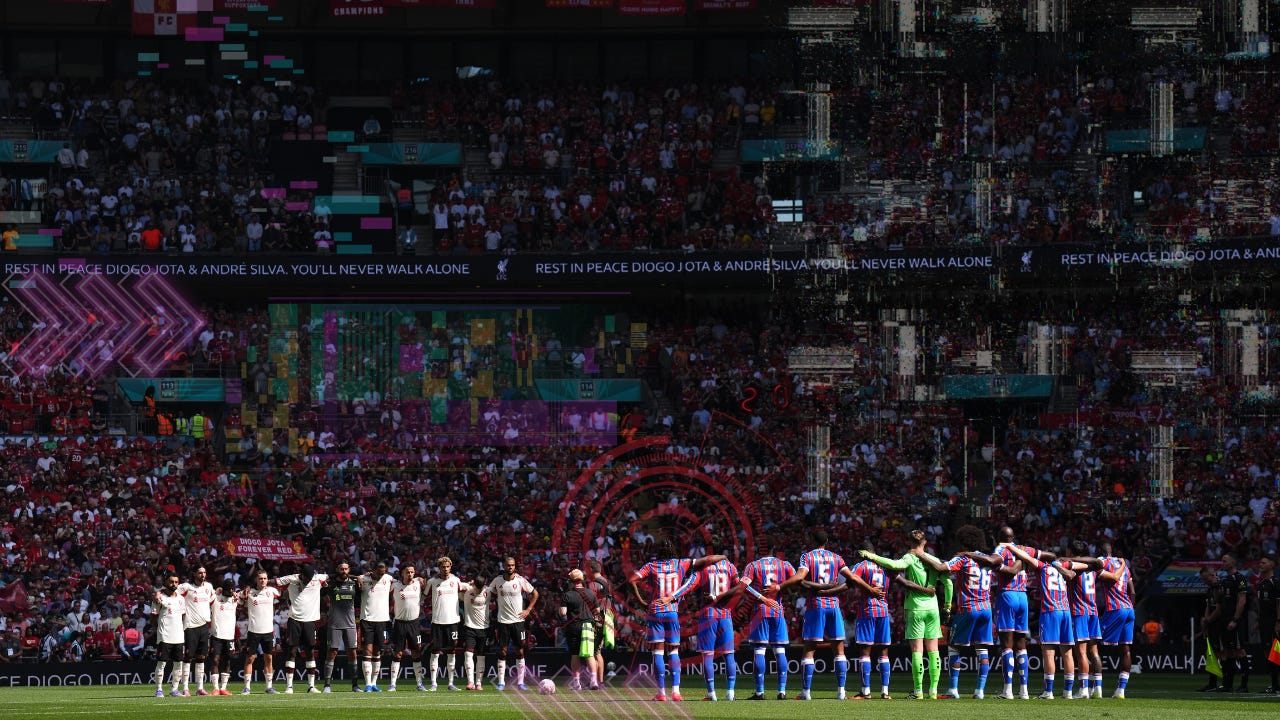

Last weekend, as English football took its first lap of a new season, 220 players and 452,669 fans took part in a shared ritual across the country. The players stood shoulder-to-shoulder in a semi-circle near the centre of the pitch, their bodies forming a broken ring against the grass. The fans rose from their seats. On cue, heads bowed for a minute’s silence, mourning Portugal and Liverpool footballer Diogo Jota, and his brother André Silva.

The air was heavy even at Old Trafford, home of Manchester United, Liverpool’s sworn rivals. And at the Bramley-Moore Dock Stadium, Everton’s gleaming new home on the banks of River Mersey, where the blue half of the city wakes up cursing the reds. At the Molineux Stadium in Wolverhampton, Rúben Neves stood like a man at a funeral - black shirt, black sunglasses that sealed away whatever was happening behind his eyes. He was Jota’s teammate, best friend, brother. Beside him, Rute Cardoso, Jota’s wife, trying to hold herself together in front of thirty thousand strangers.

This was no ordinary, performed tribute. This was deeper, heavier, coursing through the veins of those who knew Jota as a friend and a colleague. Mohamed Salah’s jaw was taut, braced to not break; Virgil van Dijk’s hands clasped and unclasped. Even the opposition players - men who had marked Jota, fouled him, pushed him over the touchline - stood with the same hollowed expression. They had expected to see him walk out in the Liverpool red, harassing defenders and scoring from half-chances. Now, he was there, but as a monochrome cutout on the electronic screen.

When the minute passed, the air broke open with applause, a thunderous roar for Jota and Silva, and a few more seconds of catching breath before the speakers returned to The Beatles, John Denver, and Oasis.

In the early hours of July 3, 2025, Diogo Jota and André Silva’s car veered off the A-52 road in Zamora, northwestern Spain, and caught fire. A burst tyre while overtaking, the authorities said. Jota and Silva died on the spot. Jota was 28 years old, still basking in the afterglow of a successful Premier League season, married just eleven days earlier to his childhood sweetheart Rute.

Since that awful morning, football has searched for ways to honour Jota, however it can. Liverpool announced that they would retire the number 20 shirt across all levels of the club. They will also pay through the remaining years of Jota’s contract, ensuring financial security for his young family. Chelsea, after their Club World Cup triumph, announced that a significant portion of their prize money would go to the Jota family fund. It didn’t matter that neither Jota nor Silva have ever worn a Chelsea shirt.

For a brief moment, the industry of perpetual motion stopped in its tracks, forced to reckon with the rawness of mortality. Even the television broadcasters, those relentless merchants of hyperbole, let the silence breathe without commentary, without graphics, without the nervous filling of dead air.

Everyone seemed to understand that rivalry and competition only go so far. Before all, we are companions in the dance against time. It sounds perverse, given the gravity of the incident, but there is something beautiful in seeing sport knowing when to stop being sport.

On 27th November, 2014, Brendon McCullum was in Sharjah, leading New Zealand in a Test match against Pakistan, when news slipped through from Sydney: Phil Hughes, the 25-year-old Australian batter, struck on the head by a bouncer two days previously, had died. Neither team took the field on the following day.

“It felt like he was one of us,” McCullum told CricketMonthly. “It was this horrible feeling of knowing it could have been any one of us. We didn’t want to continue. I was looking around the sheds and thought there was no way we could get these guys in the right space to play cricket.”

Over the next few weeks, tributes poured in from every corner between Mumbai, Manchester, and Macksville. Bats were left in the open, leaning against walls like a sword tribute. At every ground, when the scoreboard showed 63, play would pause - Hughes was on 63 when he took the blow. Players raised their hands skyward after centuries, after five-fors. The Indian Test team, in Australia for a long and fierce tour, sat in the back rows of a country church in their black suits.

The grief was intimate, collective. New Zealand did not bowl a single bouncer for the entire Test in Sharjah. The Pakistan bowlers celebrated their wickets in silence. They were playing through this game because they had to. After Australia took the last Indian wicket in the Test match at Adelaide, they gathered at a spot on the field where 408 - Hughes’ Test shirt number - was marked with paint, and formed a huddle.

Nearly six decades back, a young Manchester United team, called The Busby Babes after their famous coach Matt Busby, were on a flight out of Munich. They had just drawn with Red Star Belgrade and booked their spot in the European Cup semi-finals. Munich was a refuelling pit-stop. On the runway, snow had been falling, turning to slush. Two attempts to take off were aborted. On the third attempt, the plane skidded, lost flight, hit a hut and exploded. Twenty-three passengers were killed instantly, amongst them eight United players, three club staff, eight journalists, two crew, and two other passengers. Duncan Edwards, 21 and fresh-faced but already a talisman for the team, perished after two weeks in the hospital.

A generation wiped out in seconds. Each year, the story is retold: Matt Busby and Bobby Charlton dragged from the wreckage; the slow, stubborn resurrection of Manchester United from the charred rubble of Munich; the crescendo, exactly a decade later, of the European Cup title. It’s a parable of an institution rising back from literal debris. Somewhere in the footnotes, buried underneath the sorrow of losing a team, is the story of Real Madrid.

Real Madrid were, at the time, simply the biggest football team in the world. One scroll through their lineup and you instantly understood the Spanish translation for “Real”. They had won the European Cup in its first two years of inception - 1956 and 1957 - and they’d win it for the next three years too.

When word of Manchester United’s devastation reached Real Madrid, President Santiago Bernabeu dispatched more than just condolence. He offered a memorial pennant for the fallen, fundraising friendlies played at a fraction of their worth, and the gates of Madrid’s facilities thrown open for the wounded and grieving. In a gesture whose generosity bordered on myth, Madrid even offered to loan their legends - Ferenc Puskás and Alfredo Di Stéfano - should United need rebuilding in muscle as well as money. Regulations made such loans impossible, but the intent was like a torch in the depth of night’s darkness. For a moment, the greatest club in the world shed all their royal robes and became simply a companion in sorrow.

While reading stories like these, the mind pings to George Orwell’s famous denunciation of sport as “war minus the shooting”. The metaphor can be loosely-thrown, so it’s worth reading the excerpt in whole.

“As soon as strong feelings of rivalry are aroused, the notion of playing the game according to the rules always vanishes. People want to see one side on top and the other side humiliated, and they forget that victory gained through cheating or through the intervention of the crowd is meaningless. Even when the spectators don’t intervene physically they try to influence the game by cheering their own side and ‘rattling’ opposing players with boos and insults. Serious sport has nothing to do with fair play. It is bound up with hatred, jealousy, boastfulness, disregard of all rules and sadistic pleasure in witnessing violence: in other words it is war minus the shooting.”

It’s quite tempting, when surrounded by all this warmth, to denounce Orwell's metaphor instead, to call it the lament of a man in constant friction with the world around him. To say, look at Madrid’s outstretched hand, look at the bats leaning against walls, look at fast bowlers refusing to bowl bouncers. Look at how grief makes us human again.

But here’s the thing about moments of grace in sport - they are so memorable precisely because they interrupt the normal order of things. We document them, mythologise them, pass them down through generations because they are diversions from the script. The very tenderness with which we preserve these stories reveals what we know but don’t often say: that sport, most of the time, is exactly what Orwell said it was.

Thirty minutes into the season-opener at Anfield, thirty-two after the most hair-raising, poignant rendition of “You’ll Never Walk Alone”, a Liverpool fan from the wheelchair bay flung his chewing gum and a racial slur towards Bournemouth’s Antoine Semenyo. The Semenyo incident came two evenings after Tottenham Hotspur’s Mathys Tel was racially abused by his own fans after missing a penalty in a title match.

This is a rot, not a bruise.

The anti-discrimination and inclusion charity, Kick It Out, has some grim numbers. In the 2024/25 season, they received 1398 reports of discrimination - more than double what it was just four years ago, and higher than ever before. It is a sickening climb from the previous season’s 1332, itself a record at the time. Racism now arrives in a bomber-jet formation, flanked by transphobia, faith-based abuse, sexism - the whole taxonomy of dehumanisation.

Unsurprisingly, hatred has its own vernacular everywhere.

In 1993, the touring England Test team played a practice game against the Indian Board President’s XI in Lucknow. Screenwriter and lyricist Varun Grover was a wide-eyed thirteen-year-old sitting in the stands. His observation came in two parts. Part 1 was the heckling directed at England bowler Chris Lewis. “Lewis, the renowned fast bowler of Guyanese-origin from England, was getting abused by a section of the viewers in the stands,” Grover writes. “The abuses were racial slurs like Kaalu. Mocking dark-skinned people is an evil that has morphed into a kind of cultural trait in India — but I still found it strange that an international player of a game we all worshipped could also be at the receiving end of it.”

The other incident was closer home. Vinod Kambli, 21, was in flying form until he was hit by a ball and had to retire hurt. The fans erupted, first throwing frustration, then abuse, most of it about his caste and skin-colour.

“The most-promising player of the most-elite club of our own country was reduced to his assumed (‘lowest’) caste identity by a crowd of ordinary men who derived this power from the accident of their birth.”

Two decades later, in February 2015, Chelsea were in Paris to play Paris Saint-Germain in the Champions League. Before the match, at the Richelieu-Drouot metro station, a group of Chelsea supporters prevented a black man from boarding the train. They pushed him off repeatedly while chanting about being racist and liking it that way. Someone filmed it on their phone - the evidence that would later lead to banning orders and criminal convictions. What stayed with you, watching that footage, wasn’t just the violence but the joy in it. These men were having fun. They’d traveled to Paris to watch Didier Drogba and John Obi Mikel - both black, both African - represent their beloved Chelsea. The cognitive dissonance didn’t trouble them. It never does.

Zenit St. Petersburg, one of Russia’s oldest clubs, turned prejudice into policy. Until 2012, the club had never signed a Black player, never signed a gay player (that they knew of), never signed anyone who wasn't white and straight. Their largest supporters’ group, Landscrona, wrote manifestos about maintaining the team's “identity.” When the club finally signed Hulk and Axel Witsel, both non-caucasian, the ultras unfurled a banner: Leadership is white. In Italy, the monkey chants became so routine that Mario Balotelli once threatened to walk off the pitch mid-game. Belgian forward Romelu Lukaku was told these sounds were “a form of respect, a part of culture.” In England, it is common to hear fans referencing Hillsborough and Munich when their team comes up against Liverpool or United.

And yet, you’ll find incredible reserves of humanity within those in the middle of the ring. Even as they hear the monkey chants, the jabs about their beard and its association with 9/11, even as they feel spit land on their back when they go to the corner flag to pick up the ball.

Under normal circumstances, the 2025-26 Premier League season would’ve started with the Anfield crowd roaring Liverpool’s players onto the pitch and Thin Lizzy’s The Boys Are Back in Town booming through the speakers. But this season isn’t going to be normal for Liverpool. The club with grief and loss sewn into its fabric will be defending their league title in a season that will be defined by the grief of losing their player and friend.

Since the restart, Mohammed Salah has been part of four frames that deserve framing for posterity.

On 20th August, he wore a jet black tuxedo and collected the PFA Player of The Year trophy, a memento for the unmatchable honour of being voted as the best in the league by his colleagues and rivals.

A week back, on the night of the restart, as the game ticked into its final minutes, the scoreline reading a tense 3-2, Salah went on a dribble down the left hand side and side-footed the ball into the Bournemouth net with his weak-foot to seal the match. It was so typically Salah, to find a sharp edge when everyone else was sweating.

But I want to speak about two other moments.

After the curtain-raiser finished, Salah went over to the Kop End to applaud the crowd. At that moment, sixty-one thousand fans were singing, “Oh, he wears the No 20, He will take us to victory,” to the tune of Bad Moon Rising by Credence Clearwater Revival. Jota’s song. Salah shed the veil of the indestructible professional athlete and clapped along, his eyes red, tears streaming down his cheeks. He stood, clapping and crying, for the full song.

The cameras found him, of course. They always do. But for once they didn’t cut away to replays or interviews. They just held onto him, this man who scores goals for a living, standing there with his grief naked to the world.

About an hour before, Salah had gone up to his opponent Antoine Semenyo and patted him on his shoulder, silently conveying, “I get it. Fuck ‘em.” It was the smallest of gestures, barely lasting a full second. Semenyo nodded and jogged back to position. The game resumed.

There is a thin membrane between beauty and grime in sport. And sometimes, we get to see it laid bare, when Salah places his hand on Semenyo’s shoulder as someone, fifty yards away, in a similar shirt, prepares his gob of spit.

Too good, man. Did not expect the segue but it was such a smooth narrative shift. Both things, the solidarity and the viciousness, are true. What was that thing about multitudes and so on?

Gem of an essay.

"Before all, we are companions in the dance against time." Incredible essay, Sarthak. Incredible storytelling. Wow.