A Love Letter to Longform

England, India, 2025.

I’ve only ever read the quote on Pinterest, but there is truth to the idea that distance gives perspective. Proust, too, said something about beholding the universe with the eyes of a hundred others.

So I waited. For roughly 94 hours after Mohammed Siraj put a bow to the Anderson-Tendulkar Trophy (yuck), I let my thoughts settle and sprawl. Sometimes on the white expanse of a digital notepad, other times on paper, and occasionally in the bookmarks tab of my browser.

I read and re-read Osman Samiuddin and Karthik Krishnaswamy’s lush tributes to this summer. Jarrod Kimber pressed rewind and wrote 2958 thrilling words on the finale. Wonderful writers describing a wondrous occasion. On YouTube, I watched Dinesh Karthik, Mike Atherton, Nasser Hussain, Stuart Broad, and Sid Monga weave garlands.

A couple of years ago, Rahul Bhattacharya wrote an essay in praise of that Australia vs South Africa semi final in ‘99, a match so emotional and memorable watchers remember which way the shadows fell that day. Bhattacharya titled the tribute “Edgbaston is the sensation that never goes away.” I have been thinking about that title. It feels inevitable that the summer of ’25, with its five stirring episodes, will lodge itself in memory with the same warm persistence.

To do it justice would require the music and lyricism of Osman, so I will just borrow from his words: you had to binge-watch this. You could not read a book while the game played - I tried. Nor could you host a friend for ramen night and keep half an ear on the commentary. Even the ball-by-ball feed felt somewhat inadequate.

The more I think about it, the harder it hits me: tension is sport’s most seductive narrative device. Of course, we all lay prone at the altar of high skill. As a serial Tendulkar-Warne-Lara looper on YouTube, I can hardly deny that truism. But there is something electrifying about the friction when two teams push each other to the edge; punching, falling, rising, swinging, but just never letting up.

I spent my childhood watching cricket and football empires trample their opponents. One of those teams - Manchester United - has a place in my heart and jersey cupboard. And yet, I will tell you with my eyes closed that the 6-1 demolition of title-rivals Arsenal wasn’t nearly as fun as the 4-3 last-minute win against Manchester City.

This was a series like that. No one led for too long, the wind would shift every hour, and you’d be left clutching at “oooof” moments, breathless. I have no idea how one goes about describing this, but in the spirit of paying a just tribute, let’s take a hearty swing.

Chapter I: Opening Punches

Late on Monday, with the scent of champagne still twirling in the air, a Twitter user posted a survey asking for favourite moments from the summer. Quite the challenge to pick one from a wedding album-sized collection, no? I searched and shuffled and reached where I wanted to: the morning session of the first Test at Headingley. I love a good opening page.

The skies were sullen and overcast, welcoming us all to the English summer of cricket. Ben Stokes chose to field, which is a shorthand for sending the red cherry hooping and looping around Indian bats. Here was Shubman Gill’s India, surfacing for the first time. Kohli, Rohit, Ashwin gone - 300 Tests of wisdom turned into memory. Half the starting lineup had never played a full tour in England. You’d have to leaf back through generations to find an Indian Test side so undefined, so raw.

On that first morning, Yashasvi Jaiswal and KL Rahul matched the grey skies with their own steel. The ball bounced, swung, seamed, swayed, but couldn’t get them. For about a hundred and ten minutes, they stood stoic as England threw four seamers purpose-built for these conditions. It was stoicism of the 21st century, the kind that has Marcus Aurelius sitting next to Kendrick Lamar, or a couple of expansive drives wedged between twenty minutes of low-heartbeat defence. The scorecard read: 91 runs in 24 overs.

Then, as if the script demanded a stray bullet, two wickets in six balls.

Anyway, Jaiswal scored a century, Rishabh Pant scored one, and Shubman Gill went mega in his first outing as India’s Test captain. At 430 for 3, binoculars trained on the summit of Mt. 600, India hopped on a series of trapdoors and tumbled to 471 all out. In response, the English batters contributed as a chorus and finished at 465, just six short of India’s total, turning this game into a one-innings shootout.

In the second innings, KL Rahul was again at his serene best and Rishabh Pant scored his second century of the game. India reached 330-4, beginning to sketch plans for a tall target, possibly 500. Once again, they went into a free fall. They finished with a lead of 370, asking England to mount the tenth-highest chase in all of Test history. And yet, for two reasons, this felt underwhelming - one, India could've set a much taller target had they not collapsed; and two, in the last three years, England have made a habit of chasing down the improbable, most memorably against India in 2022.

It didn’t take long for the fears to amplify. By the time Ben Duckett and Zak Crawley, England’s openers and resident lumberjacks, took their first breath from hacking down the Indian bowlers, they were already halfway through. India’s fielders wore their most charitable clothes and dropped six catches, some so elementary they would get fifteen-year-olds a stern look from their coach and ten laps around the field. England chased the 370 down without sweat - a testament to their batting prowess and India’s lack of bowling options.

Losses like these sting. Not because of the lame finish, but because so much of it was avoidable. From 430-3 and 330-4, the kind of positions from where journalists begin drafting their end-of-day copy, narrative sealed, India had somehow found a route to defeat. Ben Stokes’ England, to their great credit and no one’s surprise, kept punching until the door cracked.

Chapter II: Salt and Pepper

Before the second Test at Edgbaston, where India had never won a Test match, the key question for Shubman Gill and Gautam Gambhir was writ large: how do you pick twenty wickets on these flat decks, especially without Jasprit Bumrah? They responded in an assertive tone: by packing our XI with more batters. That’s right. No Bumrah, no Kuldeep, just a parade of all-rounders.

Either way, Ben Stokes won another toss and set India to bat. Yashasvi Jaiswal obliged with another good score. Shubman Gill went bonkers and scored 269. Before the series, Gill had declared his ambition to be the best batter from his side - a tall order, given that in four and a half years he hadn’t crossed 36 outside Asia. Now, in the space of a week, he had a 147 and a 269. Captaincy seemed to fall on his shoulders like a silk scarf.

Buoyed by the extra batting depth, India assembled 587 runs. Within forty more minutes, they had England teetering at 25-3. Akash Deep, from Dehri in Bihar, made the Duke’s ball talk like he was born in Birmingham. 25-3 was soon 84-5, and the conversations went from the possibility of India winning to the enormity of the margin.

Enter: Harry Brook, 26, and Jamie Smith, 25. They started hitting, because what else do you do when your team’s in trouble and your coach has spiked hair and forearm tattoos? Their little fireworks show soon turned into a full-fledged counterattack. It threw everyone off - Gill, his bowlers, the commentators, maybe even Stokes and Brendon McCullum. Brook and Smith's partnership was worth a staggering 303 runs in 60 overs. When they finished, everyone had to break for a drink and a few breaths.

England ended 180 short, but the scorecard was incredible: six ducks, another single-digit score, a 19 and a 22, and two scores in excess of 150. Like someone pointed out here, the median and mode score was, amazingly, 0. Oh, and by the way, Mohammed Siraj picked up six wickets. We’ll come to him in a bit.

In the second innings, Shubman Gill went mega, once again. He now had three centuries in four innings. India, still carrying scars from the previous week, didn’t even bother with entertaining a target in the range of 400. They crossed that, zoomed past 450, then 500, left everyone wondering if they even wanted to set England a target, and eventually thought 608 was just about enough. Is there such a thing as too much caution? Did they leave themselves too little time to knock over England?

Thankfully not. 1-1. The plot refused to settle down, and we were going to the museum next.

Chapter III: Grow Some Balls

From the first morning of this series, a subplot had been developing. The antagonist here wasn’t a player or an official, but the cricket ball. See, cricket is a strange sport, but one of its stranger - read: charming - quirks is that even playing equipment can change, which has a significant effect on the game.

Test matches in Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Zimbabwe use the Kookaburra ball, manufactured in Melbourne, Australia. India use the SG ball, manufactured in Meerut. England, West Indies, and Ireland use the Duke’s ball, manufactured and hand-stitched in Walthamstow, London.

Traditionally, the Duke’s has been the fast bowler’s accomplice, the hand-stitched seam making it swing and seam at will. But this summer, the ball grew soft, the seam retreated, and soon its shape was more rugby oval than cricket sphere. So the complaints piled up. Bowlers grumbled, fielders joined the chorus, captains muttered, vice-captains boiled over and earned rebukes. Reserve umpires got a cardio workout from running onto and off the field with their box of new balls. Dilip Jajodia, owner of the Duke’s factory, embraced the news cycle and came out in defiance. He told Mumbai Mirror that the overhead and pitch conditions were contributing to a softening ball, not to mention the declining skill levels of the bowlers. Spicy.

Shubman Gill continued his curse with the coin and watched Ben Stokes elect to bat on a featherbed. England scored 387. Joe Root scored a century that sounded like an ASMR track, which can honestly be said about most of Joe Root’s batting anyway. Jasprit Bumrah, fresh from a week’s break, took five wickets and got his name inscribed forever on the wooden Honours Board at the most prestigious ground in the world.

Later, KL Rahul evoked the other Rahul with a century. One day, we will appreciate him in full, for everything that he is, instead of grumbling about everything that he couldn’t become. Jofra Archer came back to Test cricket after an agonising four-year hiatus and had the crowd receive him like he was Bruce Springsteen. He brought fire and thunder and bowled a delivery from the high heavens to send back Rishabh Pant. India finished with a 387 of their own. Another one-innings shootout.

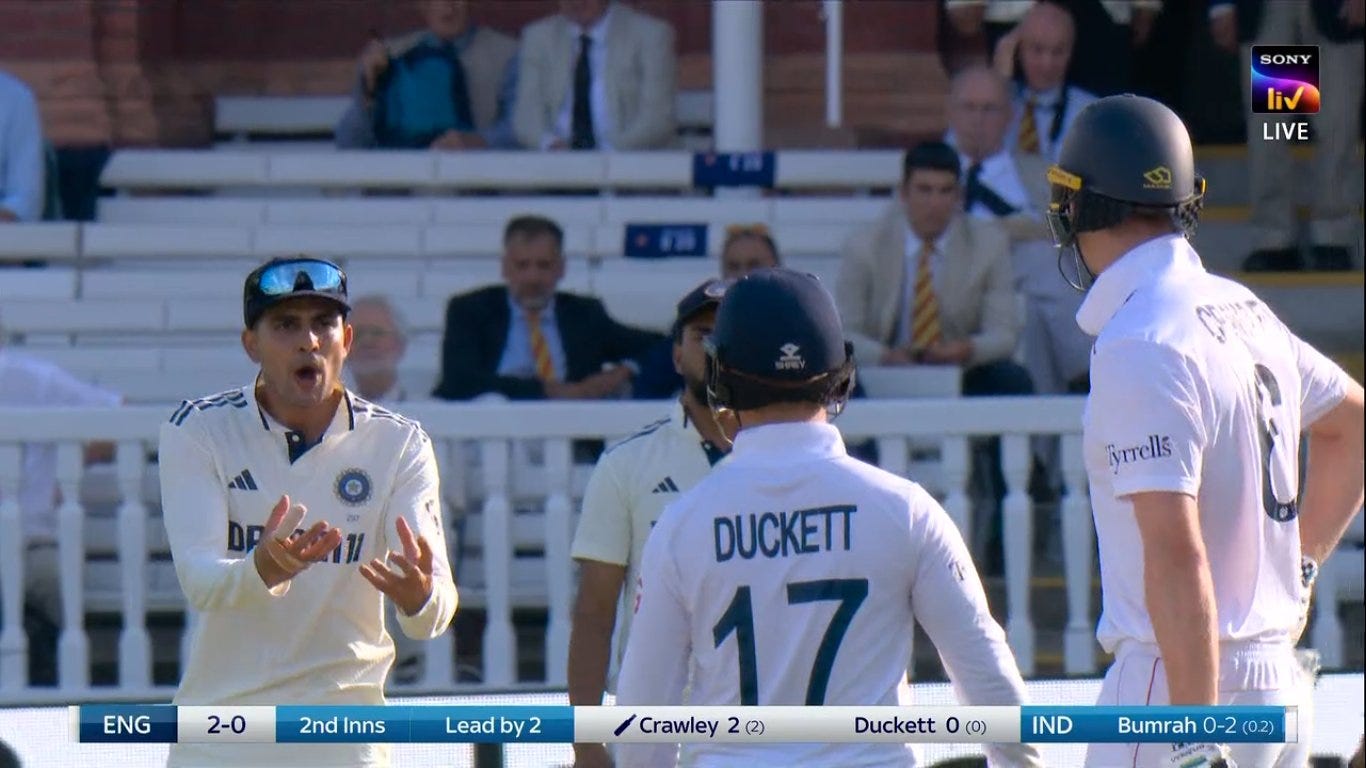

Late on day three, as the sun dipped below the Lord’s stands, Jasprit Bumrah stood at the top of his mark, lungs full, ready to unleash five minutes of hell. Crawley and Duckett, alert to the situation, stretched and yawned and made him wait. Get the clock to 6:30 and they could break for the night without having to deal with an over from Siraj too. One sledge followed the other, and Shubman Gill walked in from second slip, making a claw with his taped hands, and told Zak Crawley, “Grow some fucking balls.”

Delicioso.

The next day, England fell to Washington Sundar’s clever fingers, setting India a target of 193. Like Rahul Bhattacharya said in the Edgbaston article, such targets are booby traps. Not quite tall treks, but distant enough from a quick sprint. By the morning of day five, India were 112-8. Ben Stokes bowled as if he was caught in a fever dream. Recovering knee, recovering hamstring, but pounding the pitch at 80 mph, for hours on end.

India were still eighty runs short, which felt Everest-esque considering Jasprit Bumrah and Mohammed Siraj often looked like they’d never held a bat. Not that afternoon. Bumrah got stuck in. Ravindra Jadeja, batting with an absurd serenity for the situation he was in, took it one run at a time. No slogs, no heaves. Bumrah and Jadeja survived 21 overs, adding 35 precious runs. Mohammed Siraj walked in with India still forty-six away. A couple of glove taps, and Jadeja resumed the same stubborn song. One run at a time, farming the strike, leaving Siraj just one ball here and another there to fend off. Siraj, in turn, was middling everything. For England, Shoaib Bashir bowled unbroken with a broken finger.

You could cut cake with the tension in the air. India were inching towards their target. Over after over passed, looking like the end of India’s resistance was one magic ball away, but they just wouldn’t let go. England kept their punches coming, desperate and anxious from not wrapping up the game, but pushing until they did. Broken finger, broken legs, dehydration, exhaustion - enough reasons to loosen the grip, just not that day.

And then, Bashir bowled, Siraj middled it, and the ball backspun and dribbled onto the stumps.

2-1, England.

Siraj gazed into the distance - towards Jadeja, towards the crowd that was recovering its breath after a cliffhanger, towards his bat that had betrayed him. Eyes found him, some with awe, some with sympathy. Beaten, he folded into his haunches and punched his bat onto the pitch. Then, in a moment that will undoubtedly be framed in galleries, the English players gathered around him, arms draped in quiet solidarity.

Chapter IV: Beneath The Surface

Rishabh Pant knows pain. Everything else - his batting, wicketkeeping, records, shot-selection - can be debated into the night, but not his pain threshold.

Two days after losing his father to a cardiac arrest, Pant, aged just 20 at the time, scored a half-century for his IPL team, Delhi Daredevils. A couple of years later, he replaced MS Dhoni as a wicketkeeper, hoping that his firecracker reputation would earn him a line of credit from the fans. The fans let him know they didn’t want him. Their heckling was loud enough to make those at home squirm in their seats. Eighteen months later, after he had shaken off the Dhoni-heckles, Pant was dropped from the Test team because his wicketkeeping wasn’t considered safe enough. He came back and spearheaded India to a series win in Australia, a series they had no business being competitive in.

On 30th December, 2022, Pant was driving from Delhi to his hometown, Roorkee, when his car crashed into a divider and caught fire, leaving parts of his body charred and broken. Pant later confessed that he thought his “time in this world was over.” It was a miracle that he survived. He had to undergo reconstruction surgeries on all three ligaments in his right knee. The doctor drew up a recovery timeline of 16 to 18 months, if he was lucky. Eighteen unbearable, hopeful months later, Pant was playing a World Cup for India.

On day one at Manchester here, Pant tried to sweep a Chris Woakes delivery - because why not - and hit the ball flush onto his foot. The protrusion hinted at the gravity of the injury, which the following morning’s reports confirmed. He had fractured his toe.

The next day, Pant hobbled down the Old Trafford stairs to resume his innings. Keeping aside the debate about the practicality of risking an aggravation, this was his inner mettle laid out for the world. Fractured toes are supposed to make it difficult to even stand still. Pant whacked Archer into the stands, drove Stokes through the covers. It took another magic ball from Jofra Archer to break his sorcery.

England batted, and batted, and batted some more. They scored 669 runs, taking a lead of 311, leaving India 150 overs to survive. India lost two wickets in the first over, without scoring a run. That’s the series, then?

Not yet. KL Rahul tapped some more into his gold-laden form; Shubman Gill took his series tally beyond 700, breaking into lists that began and ended with names like Bradman and Gavaskar. But, just as they were making the 150-over trek look like a trip, both perished within an hour of each other, with a third of the incline still left to climb.

Wind behind their back, England rolled in, only to meet the defiant bats of Ravindra Jadeja and Washington Sundar. How long turned into how much longer. The two Chennai boys - one by birth, another by adoption - refused to budge. Eventually, with an hour to go for the official close of play, Ben Stokes put his hand out and walked towards the batters, offering truce and an early dinner. Jadeja and Sundar refused. For good reasons - first, because they were within sight of their respective centuries; second, because it was their chance to grind the England bowlers a little more in a congested series that had already pushed both teams to the edge of their physical limits.

England, of course, were incensed. Zak Crawley called the batters’ ambitions embarrassing, Stokes asked them if they really wanted Test centuries this way, because trust the English to decide what is the correct way to do something, and Harry Brook bowled a brand of floaty lollipops that would get you banished from backyard cricket in Cuba.

I have a theory. For all the goodwill that Stokes and McCullum’s new England team have raised through their positivity and thick paint of a #GoodVibesOnly culture, keep them out in the sun long enough and you’ll find that they are not very different from the prickly, holier-than-thou England teams from the past.

Chapter V: What’s Past is Prologue

All to play for in the fifth Test. India couldn’t win the series, but there was honour in the comeback draw. England wanted their first big scalp of the Bazball era.

Once again, Shubman called the coin toss wrong, making it a clean five out of five and the fifteenth consecutive India had ended on the wrong side of the toss. The likelihood of this happening is 1 in 32768 times. Fitting that a statistical milestone of this nature was set in a series that stopped making logical sense a long time back.

India turned up to The Oval without Bumrah and Pant. Kuldeep Yadav was once again given the reserves’ bib, reflecting a worrying pattern of risk-averse tactics and defensive team selections. We knew that the Trans-Tasman hammering through the winter would have its repercussions on the team management’s psyche. We just didn’t realise how much.

Two days before the Test, the groundsman at The Oval, Lee Fortis, got into an altercation with India coach Gautam Gambhir about trespassing onto the playing pitch. Gambhir, always irked and easily inflamed, responded to Fortis’ complaints with, “You are just a groundsman, nothing more.” Classy.

Fortis’ team had served up the summer’s first proper English-style wicket. The Indian batters walked into a greentop that promised spice aplenty. And they found out quickly enough. Every time one found rhythm, an English bowler made the ball talk and sent them back. Stuttering and stumbling, India folded for a below-par 224.

Ben Duckett and Zak Crawley thrashed the Indian bowlers like this was a T20 in white clothing. They reached 90 runs within an hour. At one point of the second morning, England were 170-3, threatening to mount a tall lead and run away with the game and series. Then they ran into Mohammed Siraj. All around him, Indian fast bowlers were dropping to injuries. Those who didn’t break physically were getting butchered on the pitch. Siraj just kept running in.

He took four in the first innings, and kept England’s lead to a manageable 23. India batted, slipped, resisted, slipped some more, and found themselves with a lead of 334 with only one wicket left. Like in the first Test, a number like that looks imposing until you remember that this England side can easily make mince-meat of it. So Washington Sundar, brimming with talent and confidence but yet to truly find a home in the Indian whites, began launching the England bowlers into the stands. One six, two sixes, third six, fourth six. It was incredible. India eventually set England 374.

On the penultimate ball of the third day, Siraj set the trap. Fielders deep, ready for the aggressive pull shot, telegraphing a clear intent for the bouncer. Zak Crawley looked around and set himself up. Then, Siraj slipped him a perfect yorker that hit the base of the off stump, sending the strong Indian crowd and ten fielders to raptures.

Early on day four, Siraj, just back on the field from a brief freshener, found himself under a skied ball from Harry Brook, then on 19. Siraj caught it perfectly, but overbalanced just enough for his trailing leg to hit the boundary cushions. Six. Should’ve been out. Like at Lord’s, Siraj wanted the ground to swallow him whole. At the end of the over, Siraj ran over to Prasidh Krishna for a hug. Sorry, man.

Brook, reprieved, tore into the bowlers. Fuck. Root scored yet another century with the calmness of a man watering his garden. He rose to second place in the all-time list of run-scorers in Test cricket. 300-3. Done.

Siraj bowled, bowled some more, and when he was done, he walked over to the boundary and put his hands to his face. This entire roller-coaster of a Test series could’ve gone so differently but for the two moments with him at the centre - the perfect defence at Lord’s, and the almost-perfect catch here.

And just then, as the bags were getting arranged, calls being made, something shifted. Brook got out to a silly shot; Bethell, nervous from the start, slogged and perished; Root edged. Hold up! Siraj asked for the ball. Once more. And then the skies poured. The umpires deemed it too much; play would have to resume the next day. Boos abound. The Sunday crowd deserved to watch this through. Everyone - the players, us, broadcasters, writers - would have to come back, once more, for the twenty-fifth day of the series. Anti-climax, perfect climax, one more plot twist - you figure it out.

Day five. Four wickets, 37 runs. London wore its darkest grey, the sky as heavy as the occasion.

Early that morning, Mohammed Siraj opened Google and downloaded a wallpaper with “Believe” written in bold font. On the last day of the Test series that had stretched all ideas of physical and mental limits, Siraj wanted to test the power of belief.

Turns out, belief, when bestowed on the right shoulders, can move mountains. Siraj was unplayable. One batter after the other perished. Chris Woakes walked out to bat with a dislocated shoulder, his left arm dangled in a sling, in the chance that his presence could be the barricade between victory and defeat. Brave man.

With the target down to teens, Gus Atkinson swung hard at a Siraj delivery. The ball soared and bounced off Akash Deep’s hands for a six. A couple of minutes earlier, captain Shubman Gill had moved out the far more agile Ravindra Jadeja and placed Akash there. Oh, what could’ve been. Siraj’s face was a portrait of disbelief. Within a few hours, he had seen both strands of the Dropped Six Experience™.

Woakes was wincing. But, just as long as he didn’t have to bat, he’d endure the excruciating pain from his shoulder bone bumping into nerves and tissues. He ran whenever Atkinson wanted him to. Brave, brave man.

Seven to get. Siraj, bowling, once again. More than 1100 deliveries in six weeks, each sent with his entire being behind it. It was beginning to show sometimes, when he lifted his shirt to his chest after a ball, panting, huffing, before walking back to the top of his mark to go once more.

143 kmph. 89 miles an hour. With a body running only on junoon, jazba, and jigra, Siraj bowled his fifth-fastest delivery of the summer.

Bowled. India win. 2-2.

In the introduction of his book Test Cricket: A History, Tim Wigmore says, “Great Tests are memorable partly because they are so rare: they require a confluence of teams playing at an equal level over several days and sheer serendipity. To produce a great series, these requirements must extend from days to weeks.”

Over twenty-five days, we got two gloriously imperfect teams, centuries, fivers, dropped catches, injuries, plasters, slings, believers, bashers, Ben Stokes, Shubman, groundsman, Gambhir, balls, ball, and an 89 miles-an-hour yorker from someone who had bowled 1100 deliveries through the summer.

The only thing missing from this album is a tied Test, and I think if there was a sixth Test in the series, the universe would’ve found a way to gift us that too.

At the post-series press conference, someone asked Shubman Gill what he thought of Test cricket. Gill wore his typical, charming half-smile and said, “In my opinion, it is the most rewarding and satisfying format.”

For you and us both, Shubman. Touché.

Wow! The rhythm of your writing, rushing when it needs to, calming down when the emotion demands it — it’s almost like a test match itself!

With this post, I continue my unbroken streak of not watching any cricket, but reading all your posts about it with pleasure.

That moment with Jadega almost brought me to tears.

Lovely post (as usual, but I have to say it again) — thank you Sarthak!

Epic piece. Well done!